A little bit of stress can be a good thing. When we’re faced with a deadline, a burst of stress can make us more alert and give us more energy to meet the challenge.

But when our stress response goes on for too long, the damage can be significant.

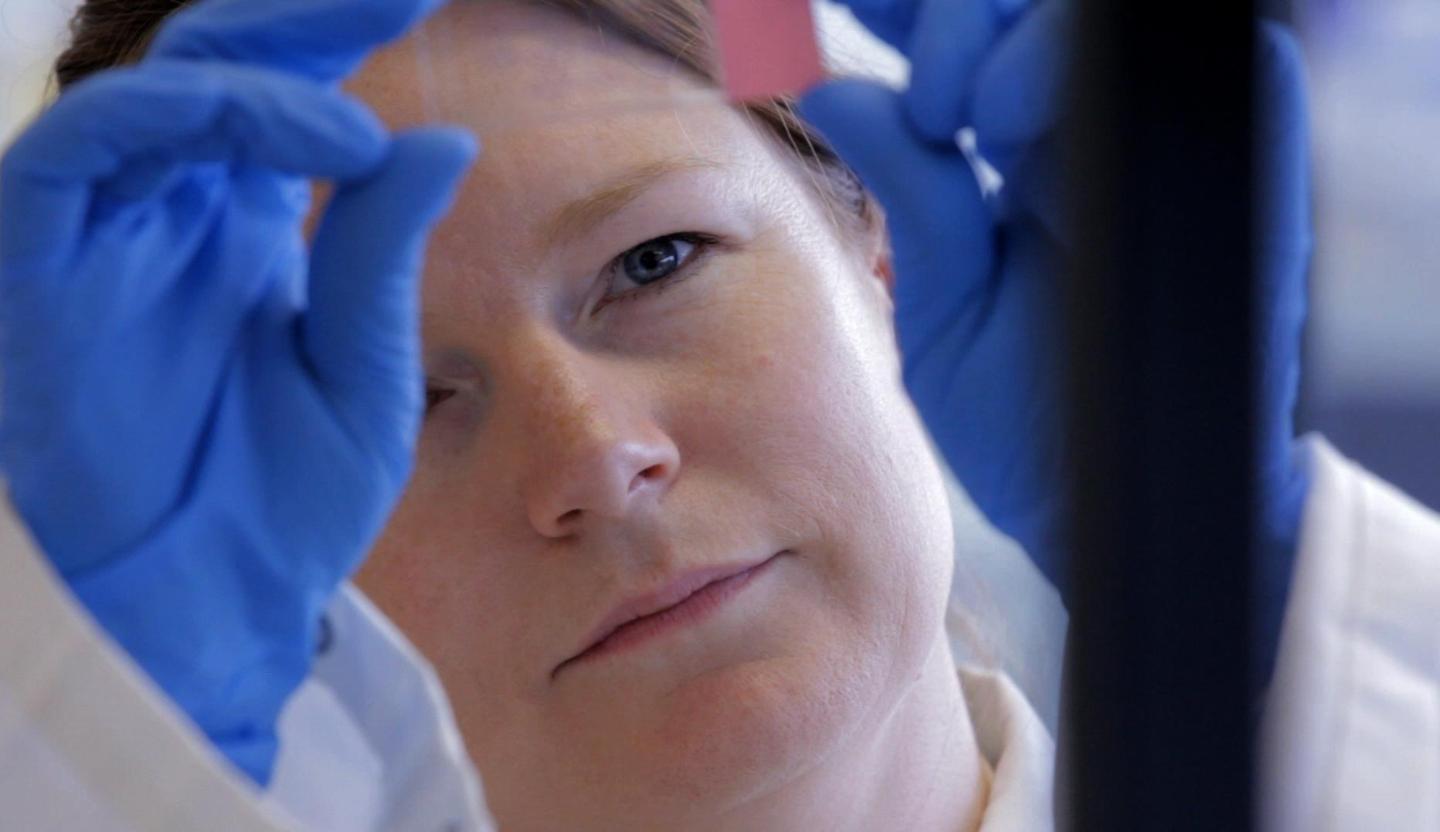

Associate Professor Sarah Spencer is an expert in stress, neuroinflammation and developmental physiology.

She shares her insights on the effect of acute stress on the human body and gives her tips on how we can take the edge off its impact.

What factors of a modern lifestyle are making us stressed?

The human body is hard-wired to react to stress to protect us from threats.

Once upon a time, this meant physical events that actually attacked our bodies like predators, disease, and violence from other humans.

Nowadays, stress tends to be caused by events that don’t physically hurt us, but merely threaten to – yet these can be just as dangerous and involve the same physiological responses.

It seems that stress is unavoidable today. But what exactly is the impact of stress and on our physical and psychological health?

Moderate acute stress doesn’t do us much harm.

The body’s responses to moderate acute stress are generally beneficial, in that they help us combat the stress (including physical stressors like disease and injury, but also psychological stressors like public speaking) and bring our bodies back to equilibrium again.

These responses help us make sure we stay away from dangerous situations and that we remember how to handle them if we encounter them again.

However, when the stress is very severe or continues for a very long time, it can become chronic and that’s when it can negatively impact our health, including increasing blood pressure, increased vulnerability to heart disease.

It can also cause atrophy of key brain regions involved in memory – ultimately negatively affecting our ability to remember, and even making us more likely to overeat and put on weight.

Everybody experiences stress at some point, but are particular people more vulnerable to its effects? Are there any differences in the way women and men respond to stress?

Stressors can be somewhat specific to life stage.

For example, one of the biggest stresses a baby can undergo is being removed from its mother, or if the mother is unresponsive to it.

For an adult, new social situations or social pressures (such as public speaking) can be particularly stressful, but this can be different for men and women.

Women tend to have higher stress responses to a social stress challenge, such as being rejected by their friends, while men generally have higher responses to achievement-based challenges, like mathematical tests.

What key hormones are at work in our bodies when we are stressed and what are their roles?

Adrenaline and cortisol are the two most well-known.

Adrenaline is released from the adrenal gland very quickly after a stressor is encountered and increases heart rate and breathing, diverting blood to your muscles so that you’re ready to run away or fight.

A few minutes later, cortisol comes along and does things like mobilising energy, enhancing memory and feeding back to shut the stress response off again.

Everyday stress becomes chronic stress when the resting cortisol is higher than normal, or when cortisol or other stress hormone responses are higher than you would expected. For most people this happens gradually rather than switching suddenly, and the timing and severity can depend on what’s causing the stress.

During chronic stress, cortisol can be detrimental. It stimulates appetite so we eat too much, suppresses the immune system so we find it hard to fight off infection or disease, and it can affect how our brain works so we can struggle with memory.

How can we manage stress better when we’re in the middle of a stressful period - facing exams or pressure at work - to minimise the long-term impact of increased cortisol?

Of course, it’s difficult to tell someone “don’t get stressed,” but we can employ certain buffers to try to make sure stressful events aren’t as hard on our bodies as they might otherwise be.

These will differ for every person, but maintaining positive social relationships is the best-studied of these in humans. Having good social support can certainly buffer against the negative effects of chronic stress.

Doing something that provides a mildly challenging distraction, without being too challenging (and so ending up being stressful in itself), is quite effective. This can be sport, playing a musical instrument or games that challenge you.

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle and a healthy body weight can also be helpful, since we know that while stress can drive obesity, obesity can also drive stress.

What have we yet to learn about stress and the human body?

There is lots still to learn. We’re just starting to realise that the body may respond to stress differently at different life stages. We know next to nothing about stress in old age, where the contribution of sex hormones falls off.

Our lab’s most recent work looks at the capacity of the ‘hunger hormone’ ghrelin to reverse the detrimental effects of stress on reproduction.

Ghrelin is a metabolic hormone that triggers feelings of hunger, increases food intake and promotes fat storage. It’s also released when we are stressed; ghrelin is part of the reason we want to eat when we feel emotional or under pressure.

The project examined the role of ghrelin in responses to immune stress. We have shown that ghrelin is important in stimulating cortisol to be released into the blood stream, but it has independent effects on the immune system.

These findings might be important for using ghrelin to combat the response to an immune challenge, like a bout of gastro, while leaving the responses to psychological stress intact.

We are also just starting to get an understanding of the gut microbiota’s importance to brain function and their contribution to the stress response.