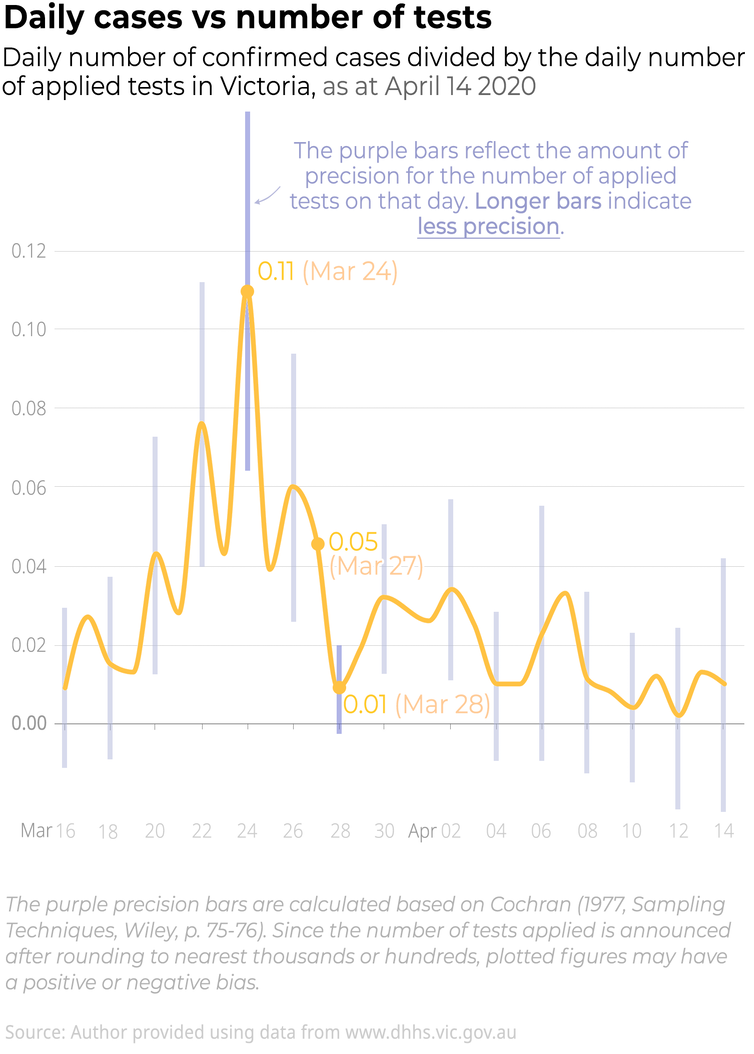

The peak is now on March 24 when the number of tests is included. If we just look at the daily count, the highest number of confirmed cases was on March 27. When we look at the percentage, it shows a decrease rather than an increase with more than 2,300 tests.

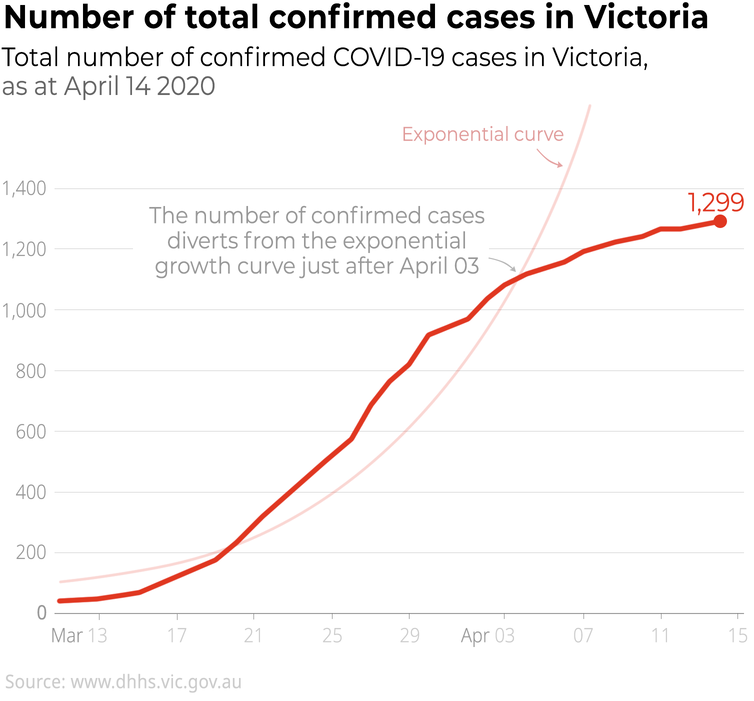

From the daily new cases data it looks like there is a strongly decreasing trend in the number of confirmed cases between April 2 and 6.

But we do not see the same strong downward movement in the percentage data on the number of tests. Although both figures go down, then up slightly, the percentage trend downward is not as strong as the daily trend.

This is a good example of the discrepancy between the inferences from the raw and percentage data. When we consider the number of tested people, we get a different view on the progress of the pandemic.

More tests needed

In using the number of tests to get a more reliable picture of the situation, there is an important point to consider. That’s were the purple error bars in the graph (above) come in.

They show the margin of error where each percentage estimate swings for the daily number of applied tests, so the actual number could be higher or lower but within those purple bars.

When we have a larger number of applied tests, we get a reduced margin of error, and that gives us a clearer picture of what is happening.

Since the peak on March 24 is backed up by only 500 tests, it has the largest margin of error. The figure on March 28 is based on 8,900 tests with a very small amount of error.

To get a more reliable picture of the situation, the number of applied tests has to be expanded, which it is what is happening in some states. This should reduce the margin of error.

Out in the community

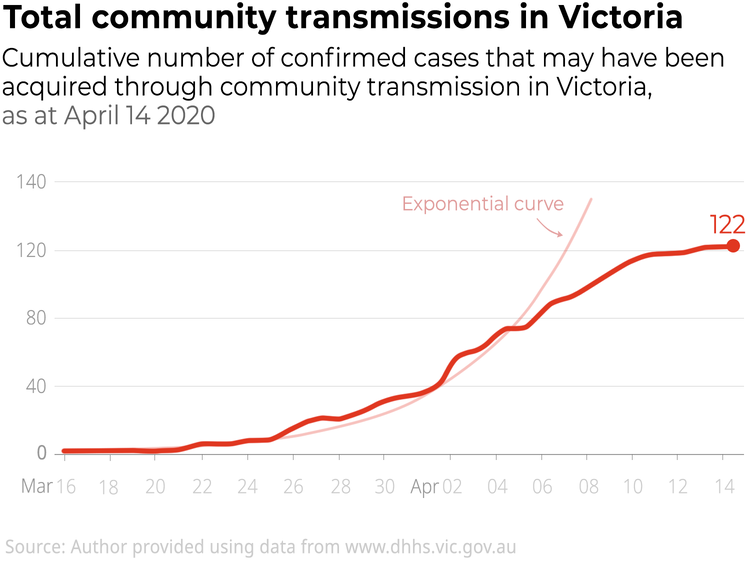

After getting some signals of flattening the curve in Victoria and Australia as well, do we see an exponential increase in just the community transmission?

Community transmission is where someone has caught the virus locally, not an infected traveller who’s returned from a cruise or overseas. At the moment they are the minority of cases and authorities would like it to stay that way to contain the spread of the virus.

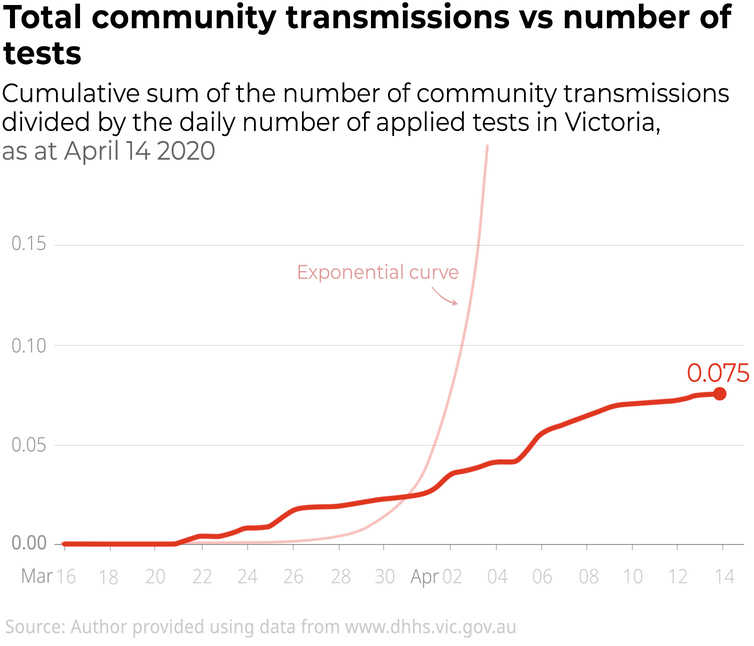

Again, we need to consider the number of tests to answer this question clearly. The raw numbers of community transmission in Victoria looked like they were increasing exponentially.