How does it work?

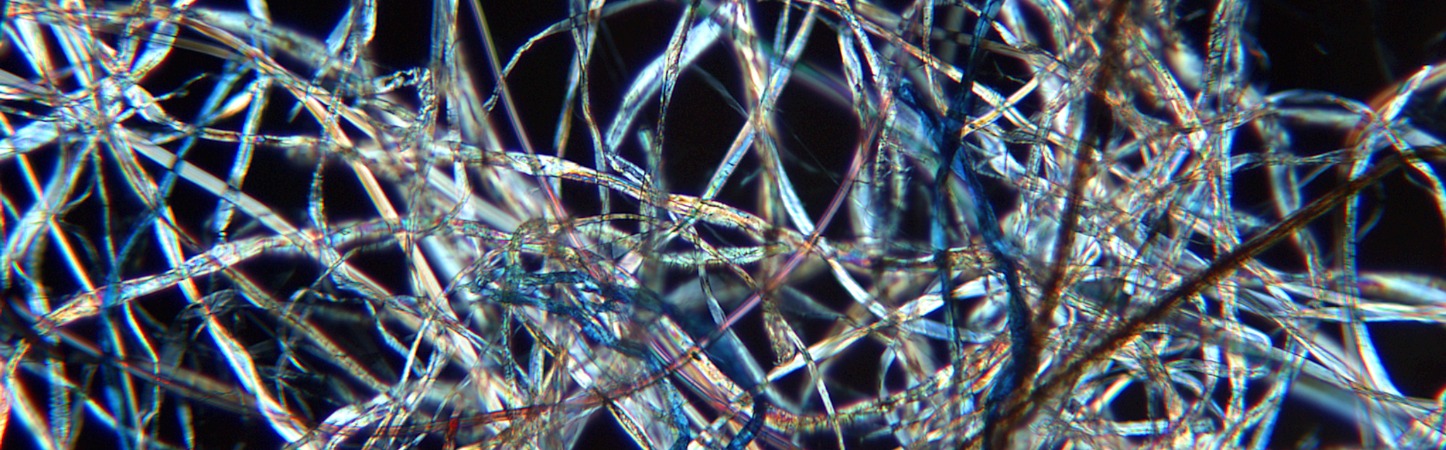

We have an intimate knowledge of the structure of textiles, how they are designed to perform, and how they behave when damaged.

Our research helps forensic scientists try to answer questions about what has happened to the textile that might give us more information about how a crime was committed: We might consider things like: Has the textile been ripped? Cut? Worn away? Does it have a stain on it?

If the textile has been washed, was it washed before or after the damage? How old is the damage? Is it five years old, or is it fresh?

If it was a strap holding down a load on a lorry that snapped and hurt the truck driver - was it the age of the strap that caused it to snap? Or did somebody cut it? What are the things that led to the failure?

How did you become a world leading expert in bloodstain pattern analysis in forensic textiles?

I worked in textiles research for many years in the United States. I had been working on modelling the behavior of individual liquid drops on fibres, when I was asked whether I could model the behavior of blood on textiles. We put together an international team and obtained funding from the US National Institutes of Justice. By combining our knowledge of textiles with forensic science experts’ knowledge in bloodstain pattern analysis, we were able to identify features that had not been seen or understood previously.

Tell us more about your research?

My particular expertise is in bloodstains. Bloodstains are a remarkably complex area of forensic textiles, because different materials can entirely change the shape of a bloodstain, depending on what they’re made of.

There’s an assumption in the bloodstain world that what you see is what was.

That might be true when blood hits a hard surface, like tiles or brick, but it can hit a textile in one shape, and then as it’s soaked up it can completely change shape.

In my research I have devised certain tools to help us better understand this phenomenon. One is a laser-guided rattrap – this is like an ordinary rattrap, but a little bigger, and heavily weighted at the base, so it doesn’t move when the spring is deployed. When we release the spring, it spatters porcine blood and we can get it to mimic how blood spatters when someone has been beaten, for example. We can then analyse how that blood has landed on a piece of fabric and been soaked up.

Another contraption we are working on is a drip tower, which is just some pieces of PVC pipe set up at different heights holding a pipette of dripping blood, designed to imitate say a bloody nose, for example, or other types of injury.

Can you give us an example of how forensic textiles is used in Australia?

In Australia, as guns are difficult to acquire most deaths that occur at the hands of another person are from stabbings or beatings, with the latter leaving clues in the form of blood spatters.

However, one area that is difficult to analyse is determining whether the stain is from the spatters or has been transferred to the accused on attempting to render aid.

There are criminal cases that have gone on for many years with the two sides arguing which it is. The accused might say, “I found my loved one lying on the floor and I tried to render aid and that’s how the blood got on me”, while the prosecution might argue, “Your blows led to the deceased's death”. So how do you prove who is telling the truth?

A knowledge of the way different textiles interact with blood can give us clues.

What is the new course that you’re running and why is it needed?

The Graduate Certificate in Textiles (Forensics) is a one-year, part time course and commences later this year.

It's designed for working professionals who want to develop specialised knowledge and skills in textile fibre identification and forensic textile analysis for crime investigation and textile fraud.

We will be providing students with training in scientific textile testing and analysis of fibres, fabrics, textile damage and degradation, and methods of textile colouration.

There are plenty of forensic experts in Australia, but at RMIT we have an in-depth knowledge of textiles in the context of crime that is hard to beat – textiles are much more complex than you might think.

What do you like about your field?

My research, in particular in bloodstains, requires a deeper knowledge about textiles than is normally needed. I’ve got a unique set of skills developed over my career for this work. We can do mathematical modelling and high-quality experiments, so that we can really delve into it in a way that nobody else has done or is able to. I sort of have the field to myself at the moment.

Story: Claire Slattery and Diana Robertson