Up to 3,400 Victorians over the past two weeks had failed to stay at home between feeling sick and getting a test, according to Premier Daniel Andrews, with COVID-19 cases continuing to rise.

However, staying at home was not an option for most essential workers, the Director of the Centre for People, Organisation and Work, Distinguished Professor Sara Charlesworth said.

One of the most essential groups of workers were lowly paid aged care workers, employed in residential aged care and in client’s private homes.

“Many of those workers are employed on a casual basis and even those on part-time work contracts are often allocated far fewer hours than they need to work each week,” Charlesworth said.

As a result, a high number of workers held multiple jobs in aged care; and for in home care, around 16% of workers held more than one job, mainly in home care or in the disability support sector.

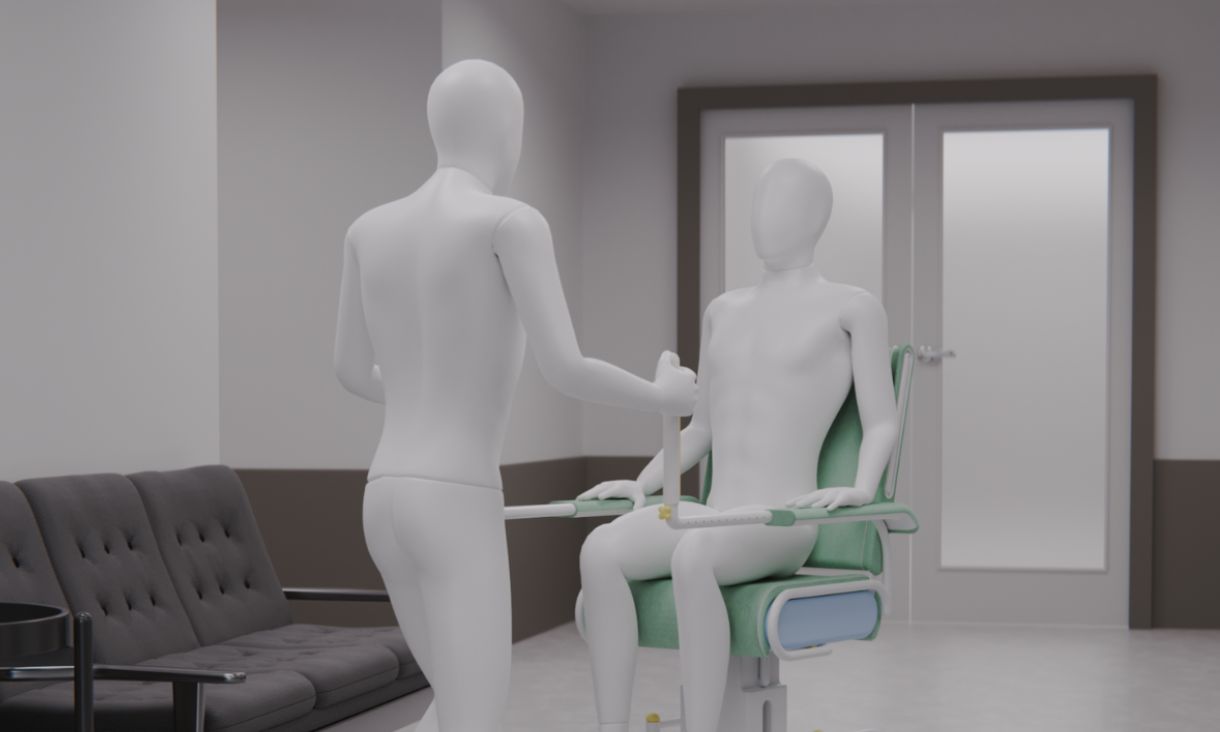

“In the COVID era going from one workplace to another, where the work entails close physical engagement with a variety of dependent clients, presents real risks to both workers and clients,” she said.

“Casual aged care workers are not entitled to any paid sick leave and in normal times most part-time workers run out of their pro-rated yearly 10 days statutory sick leave well before the end of the year.

“They simply do not have enough paid leave when they need to isolate for 14 days.

“After dismissing earlier calls for paid pandemic leave, the Fair Work Commission yesterday issued a statement referring to the clear "elevated risk" in the aged care industry,” Charlesworth said, “stating that its provisional view was that the recent developments in Victoria “would justify the grant of a paid pandemic leave provision" in the aged care award.”

However, the award didn’t cover home care workers who remained particularly vulnerable without access to regular, adequate hours of work and often without access to adequate PPE, she added.

She noted other countries had been more successful in managing the issue.

“In Canada’s British Columbia, the risks of low wages and insecure employment in aged care were seen early on during COVID-19 to be a public health risk,” Charlesworth said.

“The Provincial government in British Columbia moved quickly to not only restrict workers to one residential care home but also to support full-time employment, ensure scheduling stability and increased wages through $10 billion additional funding.”