Superbug killer: New nanotech destroys bacteria and fungal cells

Researchers have developed a new superbug-destroying coating that could be used on wound dressings and implants to prevent and treat potentially deadly bacterial and fungal infections.

The material is one of the thinnest antimicrobial coatings developed to date and is effective against a broad range of drug-resistant bacteria and fungal cells, while leaving human cells unharmed.

Antibiotic resistance is a major global health threat, causing at least 700,000 deaths a year. Without the development of new antibacterial therapies, the death toll could rise to 10 million people a year by 2050, equating to $US100 trillion in health care costs.

While the health burden of fungal infections is less recognised, globally they kill about 1.5 million people each year and the death toll is growing. An emerging threat to hospitalised COVID-19 patients for example is the common fungus, Aspergillus, which can cause deadly secondary infections.

The new coating from a team led by RMIT is based on an ultra-thin 2D material that until now has mainly been of interest for next-generation electronics.

Studies on black phosphorus (BP) have indicated it has some antibacterial and antifungal properties, but the material has never been methodically examined for potential clinical use.

The new research, published in the American Chemical Society’s journal Applied Materials & Interfaces, reveals that BP is effective at killing microbes when spread in nanothin layers on surfaces like titanium and cotton, used to make implants and wound dressings.

Drug-resistant MRSA before and after exposure to the nanocoating.

Drug-resistant MRSA before and after exposure to the nanocoating.

Co-lead researcher Dr Aaron Elbourne said finding one material that could prevent both bacterial and fungal infections was a significant advance.

“These pathogens are responsible for massive health burdens and as drug-resistance continues to grow, our ability to treat these infections becomes increasingly difficult,” Elbourne, a Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of Science at RMIT, said.

“We need smart new weapons for the war on superbugs, which don’t contribute to the problem of antimicrobial resistance.

“Our nanothin coating is a dual bug killer that works by tearing bacteria and fungal cells apart, something microbes will struggle to adapt to. It would take millions of years to naturally evolve new defences to such a lethal physical attack.

“While we need further research to be able to apply this technology in clinical settings, it’s an exciting new direction in the search for more effective ways to tackle this serious health challenge.”

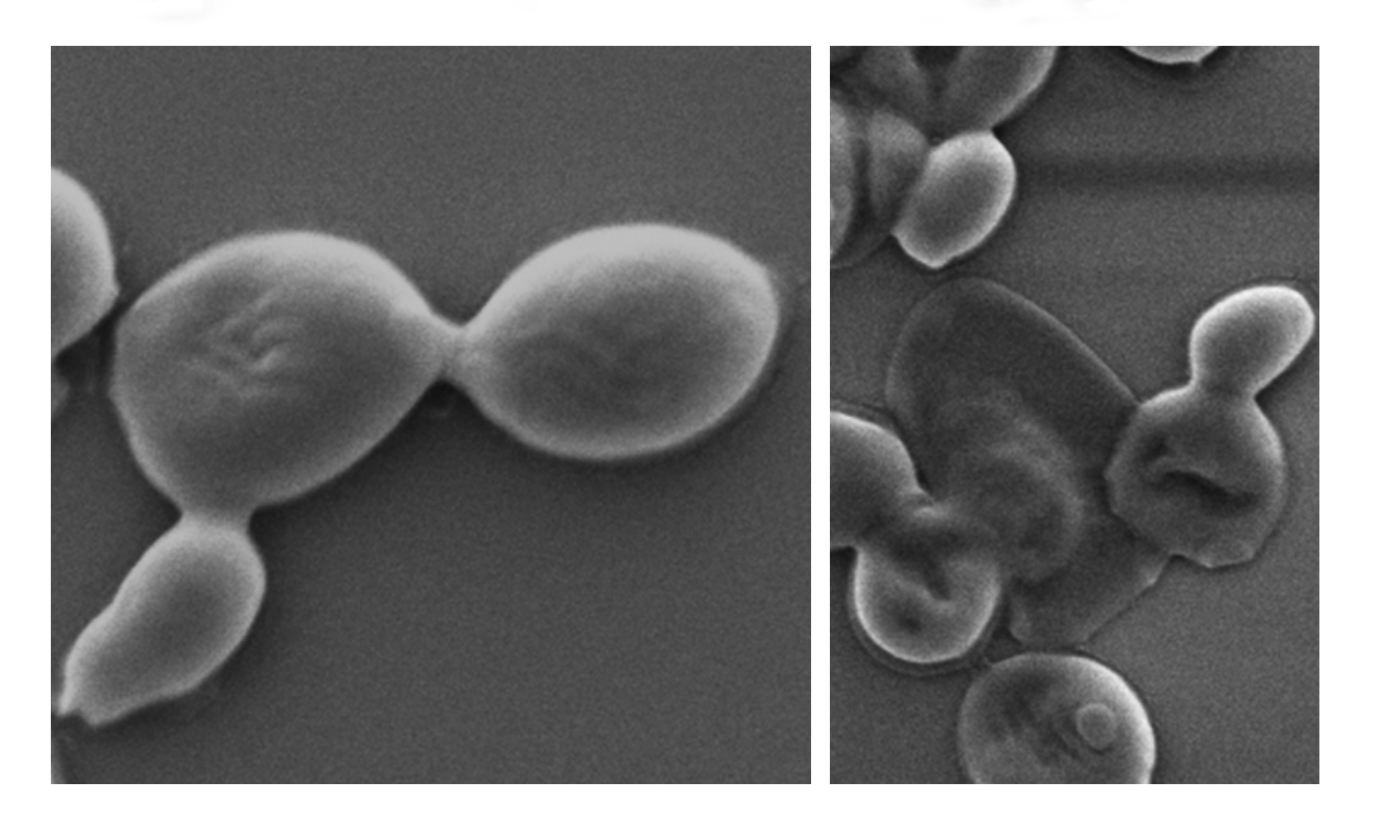

Candida auris fungus before exposure to ultrathin layers of black phosphorous (left) and after (right).

Candida auris fungus before exposure to ultrathin layers of black phosphorous (left) and after (right).

Co-lead researcher Associate Professor Sumeet Walia, from RMIT’s School of Engineering, has previously led groundbreaking studies using BP for artificial intelligence technology and brain-mimicking electronics.

“BP breaks down in the presence of oxygen, which is normally a huge problem for electronics and something we had to overcome with painstaking precision engineering to develop our technologies,” Walia said.

“But it turns out materials that degrade easily with oxygen can be ideal for killing microbes – it’s exactly what the scientists working on antimicrobial technologies were looking for.

“So our problem was their solution.”

How the nanothin bug killer works

As BP breaks down, it oxidises the surface of bacteria and fungal cells. This process, known as cellular oxidisation, ultimately works to rip them apart.

In the new study, first author and PhD researcher Zo Shaw tested the effectiveness of nanothin layers of BP against five common bacteria strains, including E. coli and drug-resistant MRSA, as well as five types of fungus, including Candida auris.

In just two hours, up to 99% of bacterial and fungal cells were destroyed.

Importantly, the BP also began to self-degrade in that time and was entirely disintegrated within 24 hours – an important feature that shows the material would not accumulate in the body.

The laboratory study identified the optimum levels of BP that have a deadly antimicrobial effect while leaving human cells healthy and whole.

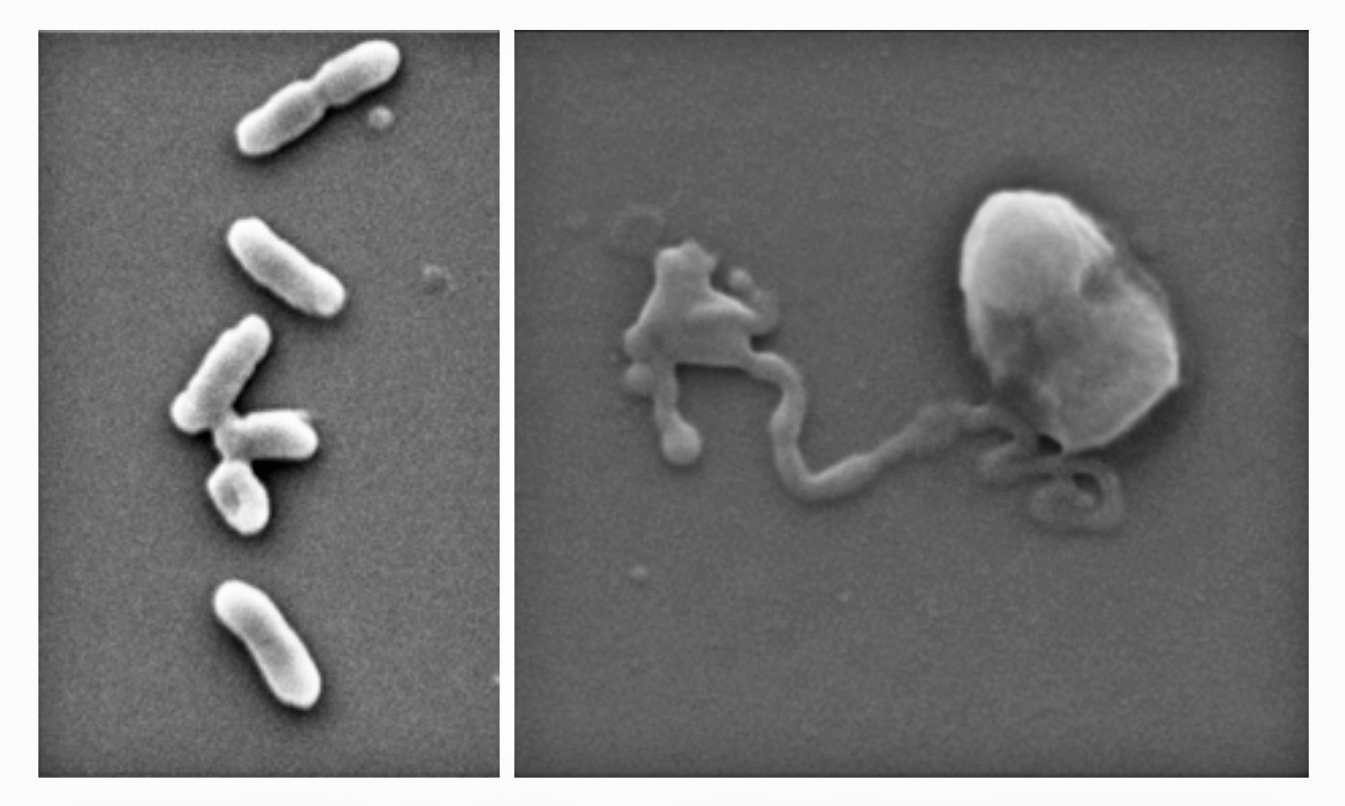

E.coli bacteria before exposure to the nanothin antimicrobial coating (left) and after (right).

E.coli bacteria before exposure to the nanothin antimicrobial coating (left) and after (right).

The researchers have now begun experimenting with different formulations to test the efficacy on a range of medically-relevant surfaces.

The team is keen to collaborate with potential industry partners to further develop the technology, for which a provisional patent application has been filed.

The RMIT research team also included: Sruthi Kuriakose and Dr Taimur Ahmed (Engineering); Samuel Cheeseman, Dr James Chapman, Dr Nhiem Tran, Professor Russell Crawford, Dr Vi Khanh Truong, Patrick Taylor, Dr Andrew Christofferson, Professor Michelle Spencer and Dr Kylie Boyce (Science); and Dr Edwin Mayes (RMIT Microscopy and Microanalysis Facility).

‘Broad-spectrum solvent-free layered black phosphorus as a rapid action antimicrobial’, with collaborators from Swinburne University of Technology and Deakin University, is published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces (DOI: 10.1021/acsami.1c01739).

Media enquiries: Gosia Kaszubska, +61 417 510 735 or gosia.kaszubska@rmit.edu.au.

Dr Aaron Elbourne, PhD researcher Zo Shaw and Associate Professor Sumeet Walia.

Dr Aaron Elbourne, PhD researcher Zo Shaw and Associate Professor Sumeet Walia.

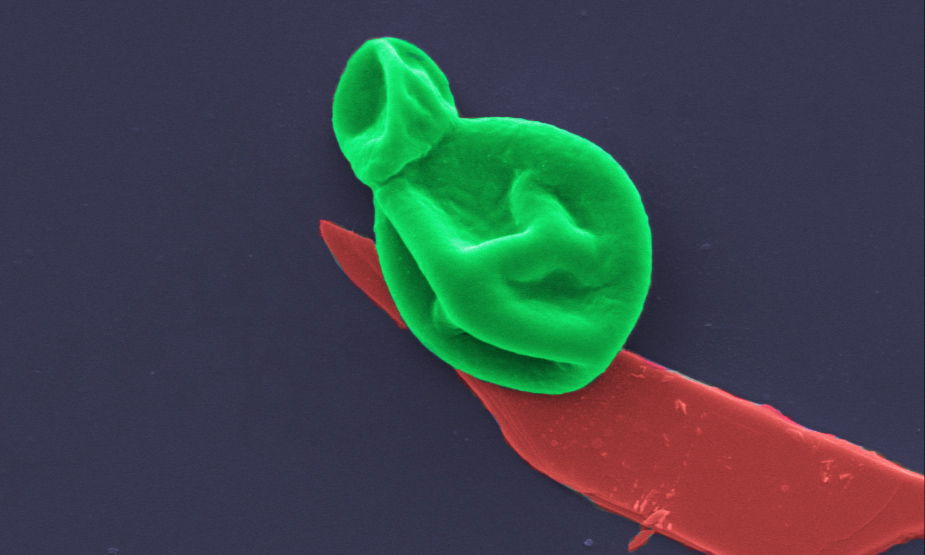

Masthead image: A fungal cell (green) interacting with a nanothin layer of black phosphorous (red). Image magnified 25,000 times.

- Research

- Nano & Microtechnology

- Engineering

- Science and technology

Acknowledgement of Country

RMIT University acknowledges the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nation on whose unceded lands we conduct the business of the University. RMIT University respectfully acknowledges their Ancestors and Elders, past and present. RMIT also acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and their Ancestors of the lands and waters across Australia where we conduct our business - Artwork 'Sentient' by Hollie Johnson, Gunaikurnai and Monero Ngarigo.