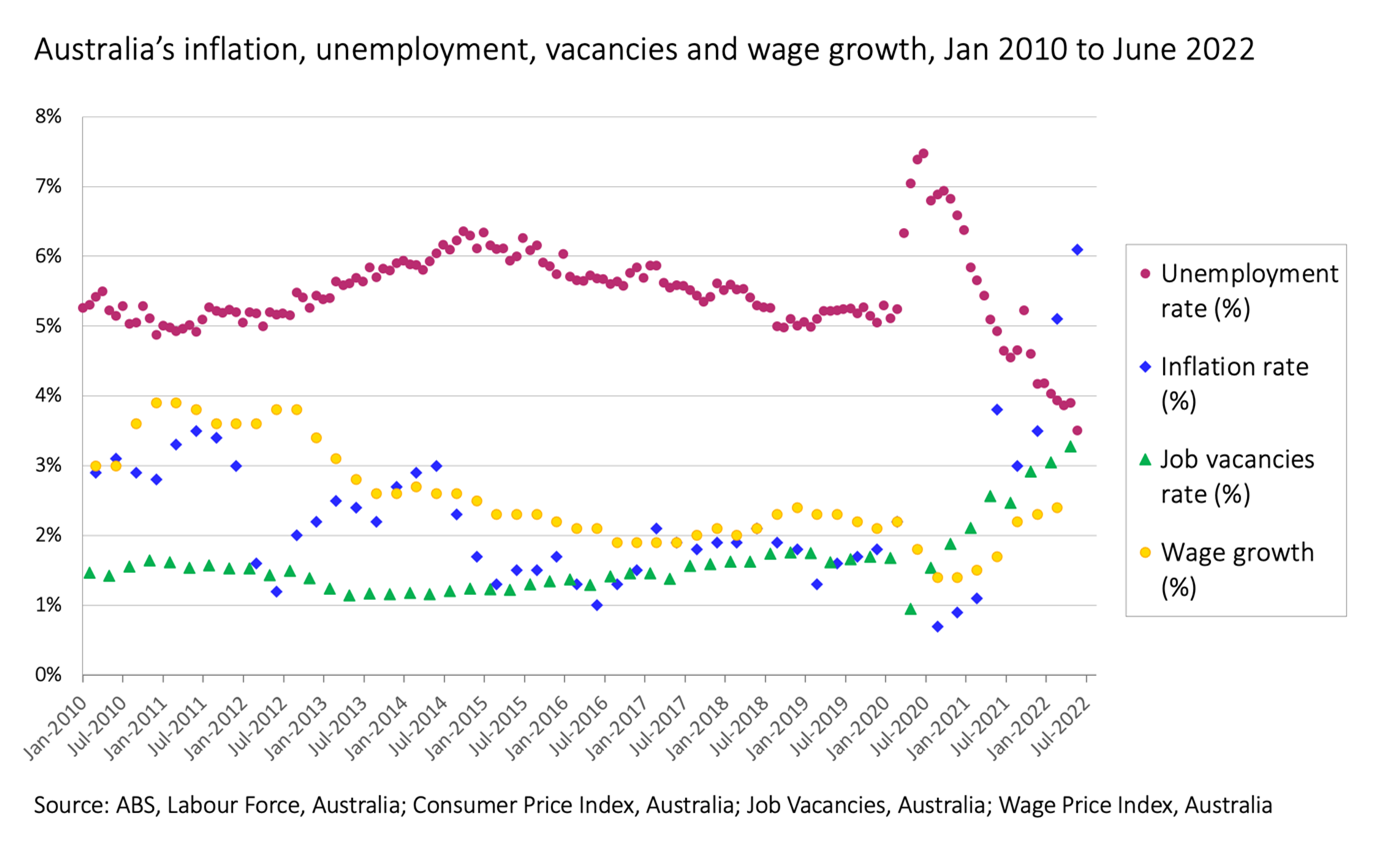

What about wages?

Even though there are clear worker shortages, wages growth is still weak at only 2.4% and is now being outpaced by an inflation rate. The gap between the inflation rate and wage growth means that workers ‘real’ purchasing power is weakening.

The logic that employers who need more workers should offer higher wages, as the way to attract and retain the workers they need, is not bear out in this current picture. It’s possible that the shift to working-from-home is distorting this link, if people are bargaining for more flexible working arrangements as a form of non-wage benefit in place of a higher wage. It is also possible that the high inflationary environment is prompting people to take any job they can get, at current wages, as a way to battle rising prices.

What can be done to ease the pressures?

Conventionally the economy’s main lever to combat higher inflation is for the central bank (Reserve Bank of Australia) to lift interest rates. While it might seem paradoxical to try to combat rising prices by making it even more expensive for mortgage owners and borrowers, that is the point. By making it costly to access credit and redirecting a larger fraction of household budget towards loan repayments, higher interest rates leave households with less money to spend on other products and reduces total ‘demand’ in the economy.

And if demand can be dialled down to be more in line with actual supply, this alleviates the need for businesses to keep pushing up prices to deal with ongoing shortages.

The dilemma, of course, is that interest rates can’t target the source of the supply-side constraints themselves. Hiking up interest rates is not going to generate more skilled workers. This instead requires is dedicated focus on supply-side factors and reigniting our economy’s productive capacity.

Among future policy directions, we need a dedicated strategy to manage COVID, so that we don't let ongoing illness and absenteeism, caring duties, and the debilitating effect of long-COVID erode our workforce productivity. On skills, we need ways to fast-track upskilling and invest in better job-matching processes. We need to do a better job of recognising jobseekers’ existing capabilities, and the broad transferability of skills from one industry to another, especially among migrants and women returning to the workforce after having children.

On wage growth, there’s a lot of talk about lifting labour productivity to boost real wages. But we need to firstly ensure we have the right industrial relations mechanisms in place that will see gains in labour productivity flow through to higher wages, instead of being siphoned off to employers or investors instead. And we need to ensure we are properly measuring the true value of workers’ contributions to the economy and wider society, especially in the care sectors and human services which are characterised by low pay, low status, and a disproportionately higher share of women. It’s possible that labour productivity has been rising in these industries – look at the workload that nurses, teachers, aged care workers delivered during the pandemic – but it’s just not being counted and valued properly.

There is, at least, no shortage of issues to explore at the Australian Government’s upcoming Jobs and Skills Summit.

The Australian Government’s Jobs and Skills Summit will be held at Parliament House in Canberra on 1-2 September. For more information, visit Jobs and Skills Summit.

Author: Dr Leonora Risse, Senior Lecturer in Economics, RMIT University