Transforming construction health and safety with SHINe

RMIT has launched the Safety and Health Innovation Network (SHINe), an industry-led collaborative research funding model to identify and tackle problems across the construction industry.

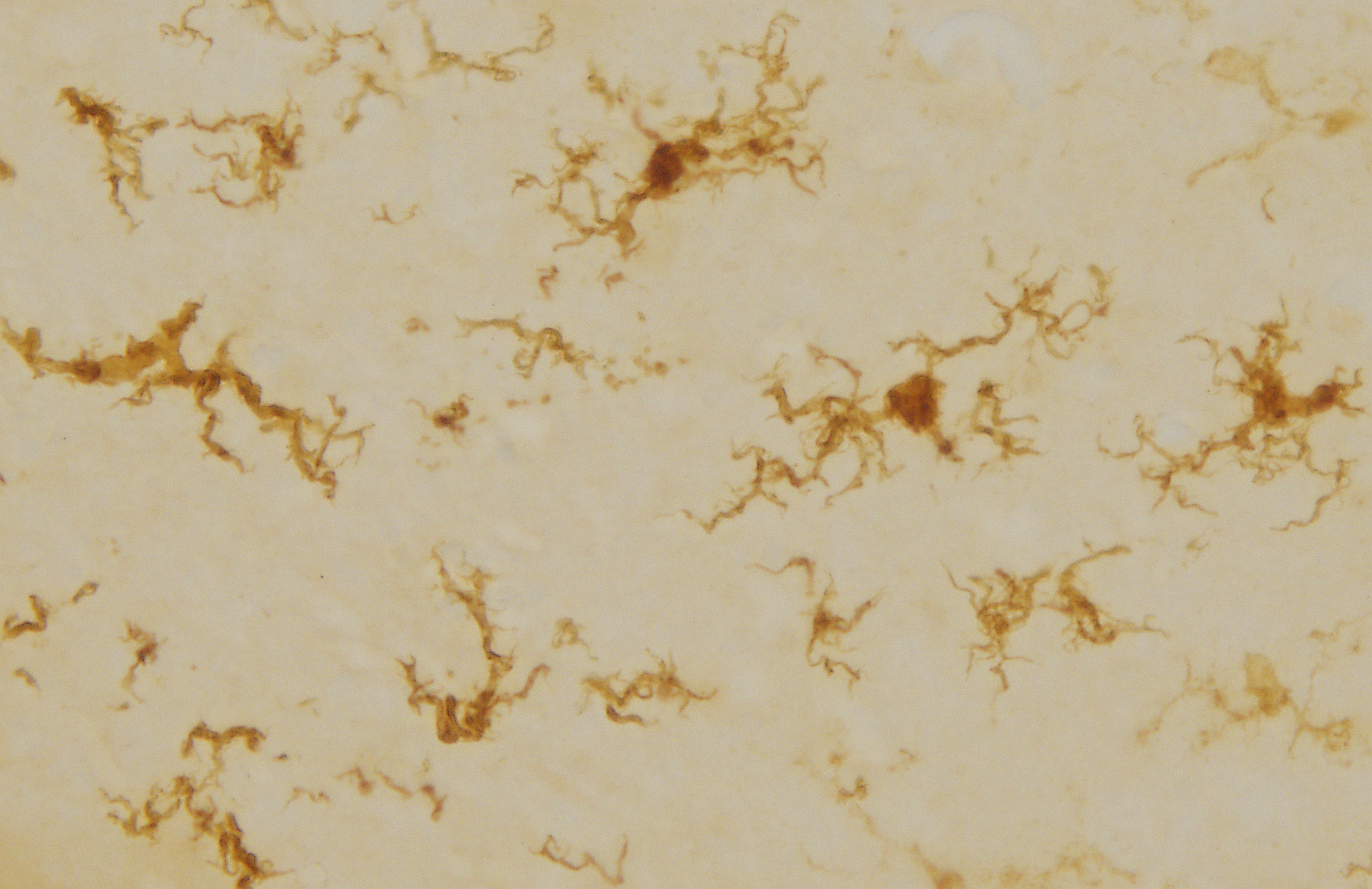

Gold beats platinum for chemo drugs in new lab study

Gold-based drugs can slow tumour growth in animals by 82% and target cancers more selectively than standard chemotherapy drugs, according to new research out of RMIT University.

Confinement may affect how we smell and feel about food

New research from RMIT University found confined and isolating environments changed the way people smelled and responded emotionally to certain food aromas.

New partnership with Cisco and Grampians Health to upskill healthcare sector

RMIT’s Health Transformation Lab and College of Vocational Education are piloting a program to rapidly upskill front-line staff, broader health workforce and IT professionals in the healthcare sector to meet the industry’s emerging skills needs.