RMIT student wins Best in Category at Victorian Premier’s Design Awards

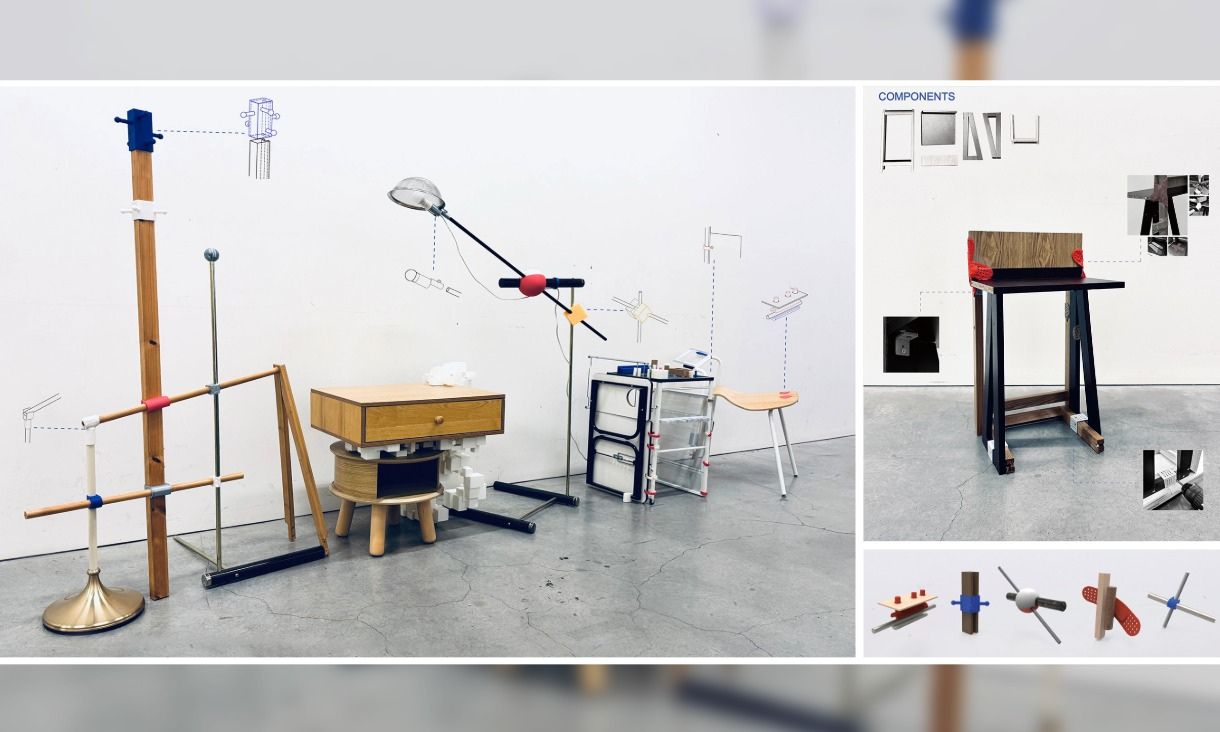

A sustainable furniture system using digital fabrication techniques and repurposed furniture waste has won Best in Category for Student Design at the Victorian Premier’s Design Awards alongside over twenty RMIT-affiliated projects recognised at this year’s awards.

RMIT takes centre stage at Melbourne Fashion Week 2025

Students, PhD candidates, staff and alumni from the University's School of Fashion & Textiles featured across a range of events at Melbourne’s signature fashion event.

Graduate weaves Melbourne Fashion Festival success

RMIT student Indigo Stuart was named National Graduate of the Year at this year’s PayPal Melbourne Fashion Festival, alongside other success from the RMIT community.

New guidelines help fashion brands cut waste and emissions

RMIT sustainable fashion experts have collaborated with brands to create guidelines aimed at eliminating wasteful designs and promoting durable fashion that supports reuse and recycling.