Call to action: A postmortem on fact-checking and media efforts countering Voice misinformation

Turning the lens on four misleading narratives, this article, coupled with additional expert advice, offers tips on how the media can help dispel disinformation effectively ahead of future democratic events.

By Renee Davidson, Eiddwen Jeffery, Esther Chan, Dr Anne Kruger

Introduction

It was not long into the Voice to Parliament referendum campaign that mis- and disinformation became a pervasive feature of social media, muddying the waters for the public by questioning factual information about the proposed constitutional change.

Following the referendum’s defeat, Indigenous leaders broke their week of silence with an open letter to the Australian government, media and public, in which they addressed the issue of rampant misinformation:

“The scale of deliberate disinformation and misinformation was unprecedented, and it proliferated, unchecked, on social media, repeated in mainstream media and unleashed a tsunami of racism against our people. We know that the mainstream media failed our people, favouring ‘a false sense of balance’ over facts.”

This led to two initial questions. First, whether Voice misinformation was countered, and if yes, how it was done and if it was enough. Second, how media reported on Voice misinformation and if their reports helped slow the spread or on the contrary, amplified it.

Additionally, with most of the misinformation and the tactics used to share it quite predictable ahead of time, how can communicators more consistently and continuously warn the public of what to expect, and what not to fall for?

This research article aims at answering these questions in three parts:

- Conduct a data analysis on the fact checks and media reports addressing four recurring misleading narratives circulating online throughout the referendum cycle.

- Seek insights from Australian media industry practitioners into the effectiveness of media reports in curbing the proliferation of misinformation.

- Consult disinformation experts on media best practices, on top of fact-checking and reporting, that can help inoculate the public against misinformation.

Distilling the learnings from the above, we highlight five practical recommendations for reporters and fact checkers to effectively correct misleading claims, limit their spread, communicate the corrective information with the public, and help inoculate the public against misinformation.

Misleading narratives

For this analysis, we selected four of the most persistent misleading narratives circulating online prior to the Voice referendum.

These narratives surfaced early in the campaign, and consistently reappeared in the months leading up to the referendum, despite being repeatedly disproven as misleading or false by fact checkers and constitutional law experts.

The narratives were as follows:

| Narrative | Number of fact checks |

|---|---|

| 1. The Voice divides the nation by race | 5 |

| 2. The Voice gives “special rights” to one race of people | 3 |

| 3. The Voice will lead to policies that favour Indigenous peoples and in turn “harm” non-Indigenous people | 10 |

| 4. Indigenous Australians already have a “voice”, either through elected officials, the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA), or other organisations and agencies serving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples | 9 |

| Total number of fact checks | 27 |

Out of the four, the longest running narrative was that Indigenous Australians already have a “voice”, which has been circulating online since at least July 2017 and resurfaced during the 2022 federal election. The other three narratives first appeared online in around late 2022 or early 2023.

The images below provide a selection of samples demonstrating how the narratives were presented online:

Part 1: Fact checks and media response to misleading narratives

1a. Fact checks

All four narratives were debunked multiple times in the year leading up to the October 2023 referendum, as seen in the table above.

Keyword searches on Google found that altogether 27 fact checks were published by Australia-based fact-checking outfits, including AAP FactCheck, AFP Fact Check, RMIT FactLab and RMIT ABC Fact Check, in response to the four narratives.

Misleading narratives were shared more often on social media than the fact checks about them

Using the Meta-owned social media tracking tool CrowdTangle Link Checker and the data extraction tool Instant Data Scraper, we analysed the number of times the fact checks were shared on Meta platforms, including Facebook and Instagram, as well as X (formerly Twitter) to assess the referability of these fact check reports.

This analysis does not track website visitor data. While web analytics tools can offer an estimate of web traffic, only the website operators would have access to the number of visitors to their websites.

In total, the fact checks were shared 4,268 times on Facebook, Instagram and X between October 14, 2022, until October 14, 2023, the day of the referendum.

According to CrowdTangle Link Checker, which shows how many times an URL is shared on Facebook and Instagram, these fact checks were shared a combined 2,734 times from their websites to these platforms.

For X, we identified all X posts containing the URL of each fact check using Instant Data Scraper. We then downloaded the dataset manually and found that overall, they were shared 1,534 times on X.

This shows that the fact checks had a relatively small reach compared with the number of times the misleading narratives were shared on the same platforms.

For example, the narrative that the Voice will lead to policies that favour Indigenous Australians was shared more than 6,500 times in one Facebook post alone, published by One Nation leader Pauline Hanson.

Fact checks were mainly shared by users trying to debunk misinformation

However, our research found that these 27 fact checks were often shared on these platforms by users trying to counter false claims made by other users.

On X for example, the fact checks were mostly shared in replies against what the users considered false or misleading information.

On Facebook, however, the fact checks were not only shared by those who agreed with them, but also users who disagreed with the findings. For instance, some Facebook users shared URLs of the fact checks alongside captions that challenged or outright rejected the reports.

The data gathered from Facebook, Instagram and X provides a snapshot insight into how inclined users were to share these fact checks with other users on the platforms. However, it does not account for the number of times the fact checks might have been shared via other means, such as newsletters, emails or private messages, nor does it take into account the existing audiences of the fact-checking outfits.

News reports highlighting fact checks might increase visibility of corrective information

Furthermore, while the fact checks might have had limited traction on the three social media platforms included in this analysis, they were reaching audiences who did not visit their websites. This is because some of their content was syndicated on another news website and featured in reports by print and broadcast media.

They might also be reaching more social media users when these news reports were shared on the platforms.

For instance, in January 2023 a fact check by RMIT FactLab addressing one of the four narratives was featured in an episode of the ABC’s current affairs programme 7.30. A corresponding article about the episode, published on the ABC website and also mentioning the factcheck, had had nearly 1,800 interactions on Facebook, according to CrowdTangle, which collected no data from Instagram. In comparison, the fact check report published on the RMIT FactLab’s website only had 66 interactions on Facebook.

Misleading narratives boosted by prominent figures continued to spread despite fact checks

Despite the fact-checking efforts and news media sharing those fact checks, the four narratives continued to travel online. It is worth noting that they might have gained more attention after being referenced by two former Australian prime ministers, as well as current and retired politicians.

Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott penned a column in December 2022 arguing that “Indigenous people already have a voice. His Liberal predecessor John Howard, meanwhile, promoted the narrative that the Voice would divide the nation by race.

On top of that, two of the narratives were also referenced in the Australian Electoral Commission’s official referendum booklet.

The No camp stated in their argument that the Voice was an “unknown” and would open the “door for activists”, adding, “some Voice supporters are upfront in saying this Voice will be a first step to reparations and compensation and other radical changes” (page 11 and 13). The narrative that the Voice would “would permanently divide Australians” was repeated multiple times, citing a comment from Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, a No campaigner, that “this Voice will not unite us, it will divide us by race” (page 11 and 13).

Some campaign groups advocating for the No case gave the narratives a boost via social media advertising, which allowed them to target voters of a specific demographic. For instance, early in the campaign one group placed nearly 100 ads on Meta platforms promoting the narrative that the Voice will give one race of people “special rights and privileges”, scoring more than two million impressions.

1b. Media coverage

To analyse Australian media’s response to the four misleading narratives, we examined broadcast segments, including radio and television, as well as online articles, including news reports and opinion pieces, that featured the relevant narratives. The data was gathered from the 12-month period leading up to the referendum.

Opinion and commentary pieces were included in our analysis given their significant presence in reporting on the Voice and when presented in multimedia reports, their ability to reach a wider audience. Like news reports, opinion pieces at times both promoted and debunked the four misleading narratives, so including them in this study gave us greater insight into how commentary reporting contributes to informing the public.

Broadcast

For broadcast, the social and media intelligence tool Meltwater was used to capture the number of Australian radio and television segments that mentioned keywords related to the narratives.

In order to set some parameters for the dataset, we excluded variations of the keywords or phrases in our searches. For example, key phrases such as "paramount rights” and "special measures" were excluded from the search string for narrative 2.

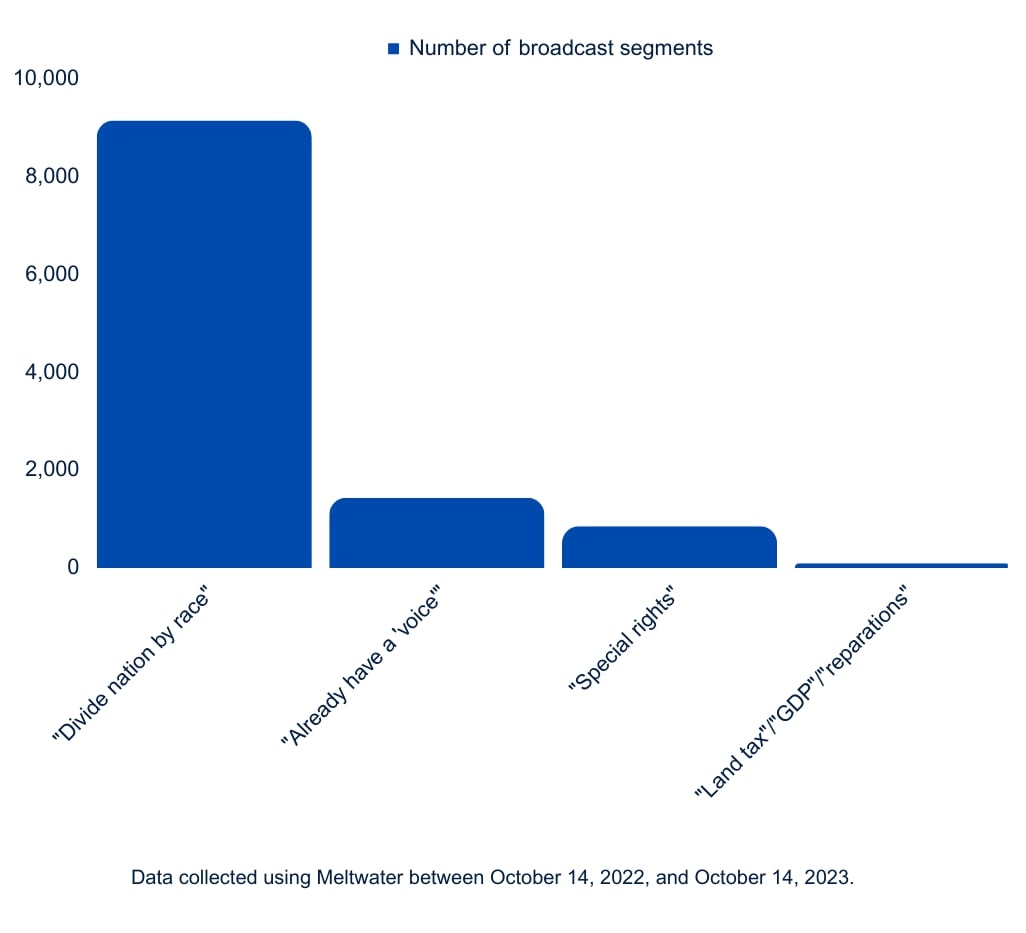

The searches returned a total of 11,525 segments aired between October 14, 2022, and October 14, 2023. The search strings we used and the number of broadcast segments that featured the narratives are as follows:

| Narrative | Note | Number of segments |

| 1. Voice AND race AND (divide OR divides) | This searches for mentions of all three items in the string, including i) the Voice; ii) race; and iii) the word divide or divides. | 9,141 |

| 2. Voice AND “special rights” | This searches for mentions of the Voice and special rights. | 852 |

| 3. Voice AND (“land tax” OR GDP OR reparations) | This searches for mentions of the Voice and one of the items in the brackets, which represents some of the policies that No supporters believed the Voice would lead to, and which they said would favour Indigenous Australians. | 96 |

| 4. Voice AND ("already have a voice" OR "already had a voice") | This searches for mentions of the Voice and the phrase in past or present tense. | 1,436 |

| Total number of segments | 11,525 | |

Presenting the data in a chart, as seen below, we noted that narrative 1 enjoyed an outsized popularity in broadcast media, appearing more than six times the number of segments than the second most popular narrative:

While a detailed analysis of these broadcast segments is beyond the scope of this research article, a cursory examination shows that even though the four narratives were misleading and had been debunked in fact check reports, they remained a popular talking point throughout the referendum campaign.

Online

For online articles, we ran keyword searches on Google and collected the results using the data scraping tool Data Miner.

We combined the search strings in the “Broadcast” section with two additional components, as seen below, to narrow our searches to include only news articles and/or opinion pieces published by most of the Australian media.

(site:.com.au OR site:abc.net.au OR site:.com)

(inurl:news OR inurl:opinion OR inurl:commentary OR inurl:inquirer)

The more generic domain “.com” was included to source content from international news agencies or organisations that have a presence in Australia, such as The Guardian, Agence France-Presse (AFP) and Reuters.

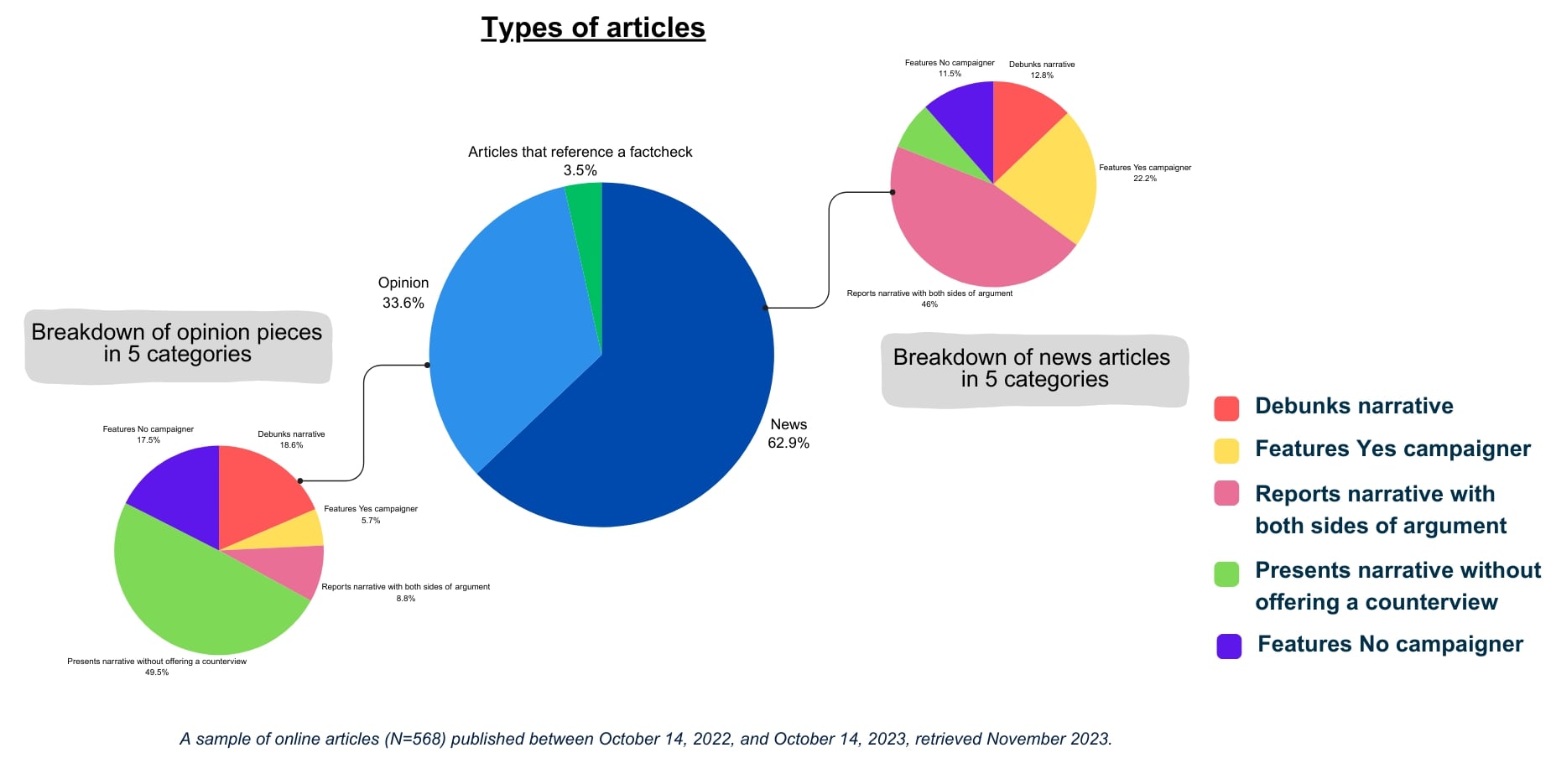

The searches returned a total of 873 online news and/or opinion articles published between October 14, 2022, and October 14, 2023. Of these, 305 were not relevant to the four narratives, leaving 568 articles for analysis.

Our analysis found that among the 568 articles featuring the four narratives, 66 percent were published on websites classified by the corresponding media outlet as “news”, while the remaining 34 percent were published on sites that were classified by the media outlet as “opinion”, including the variations “commentary” or “inquirer”.

To better understand exactly how the narratives were discussed in the media, we classified the articles into five separate categories:

- Category 1: Articles debunk narrative either through independent analysis or citing the work of experts and/or fact-checking organisations;

- Category 2: Articles feature Yes campaigner(s) dispelling narrative;

- Category 3: Articles report narrative without identifying it as false or misleading, and/or report both sides of the argument i.e. “false balance”;

- Category 4: Articles present narrative without identifying it as false or misleading or providing a counterview;

- Category 5: Articles feature No campaigner(s) promoting the narrative.

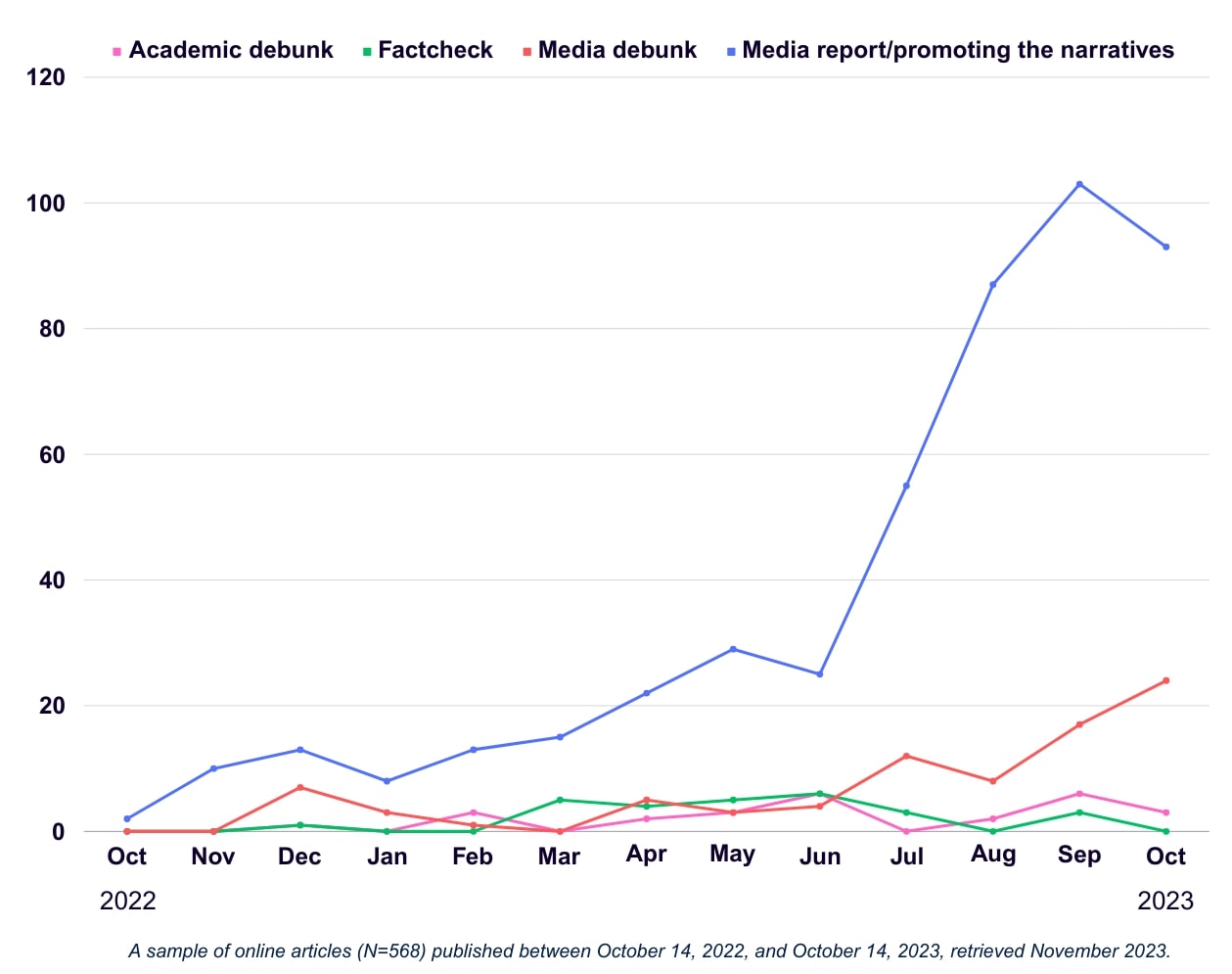

Our research found that only around 15 percent of the articles included fact checks or corrections to debunk the misleading claims (category 1), while around 33 percent of the articles fell under category 3, which is when the media presented both sides of the argument in a balanced way. This is despite the fact that fact checkers and experts had found the four narratives misleading and therefore should not have been given equal or greater weight.

It is worth noting that nearly 50 percent of the online articles that addressed the narratives (category 1) were published in the six weeks prior to referendum, even though the four narratives were shared online consistently in the year before voting day. This will be discussed in the following section when media practitioners emphasised the need for the continual correction of false or misleading claims.

1c. Academic publications against misleading narratives

Running alongside fact check reports was a significant academic effort to counter Voice misinformation, with Australian universities publishing online articles, reports, FAQs, video explainers and fact sheets on their websites and social media platforms. Academics also contributed to The Conversation, a website that publishes articles, research reports, expert commentary and analyses from academics and researchers.

Academics started publishing against the four misleading narratives in around late 2022. On average, three academic articles or social media posts were published each month in the leadup to the referendum, with a slight increase to six in June and September 2023 respectively..

In total, 29 online materials were published by academics countering the four narratives: 12 addressing the one about how the Voice would give “special rights” to one race of people; 11 on the narrative that the Voice would divide the nation by race; four against the narrative that Indigenous Australians “already had a voice”; and two refuting the one about how the Voice would introduce policies that favour Indigenous Australians.

This report does not include an in-depth analysis on how far these publications travelled online, their contribution to efforts debunking the four narratives, or the traffic the university websites got from these articles.

We note, however, that the academic publications were not often referenced in online news articles and/or opinion pieces about the Voice — we found only a handful of isolated examples in our research.

This perhaps was a missed opportunity in countering Voice misinformation as these publications included valuable expert analysis, which could have aided media and fact checkers in their reporting.

Part 2: Insights from practitioners into media efforts countering Voice misinformation

CrossCheck started tracking and analysing false or misleading narratives about the Voice since the referendum was announced, and we found that despite being debunked repeatedly by fact checkers, most of them continued to circulate online.

Our data analysis, as illustrated above, shows media efforts in addressing Voice misinformation were minimal and not consistent. Most of the articles debunking the four narratives were either “one-off” responses, or published too late into the referendum campaign (September 1 to October 14, 2023).

CrossCheck spoke to an independent Aboriginal journalist and an Indigenous writer and social commentator about their observations of media efforts to counter Voice misinformation, how they thought the media can improve its response and help build the public’s resilience against misinformation. The insights of these two experts were pertinent to this research: both are from Aboriginal-led media organisations and have a comprehensive understanding of how media reports impact Indigenous communities.

Charles Pakana, an independent Aboriginal journalist and editor at the online news site Victorian Aboriginal News, told CrossCheck in an email that the media should have adopted a more positive model perspective with regard to the Voice.

“There was incredibly little coverage given to ‘the benefits to all Australians’ as a result of the Voice — and that includes me! There should have been more work on investigating and reporting on the financial and social benefits beyond addressing Closing the Gap metrics.”

There is a need for the continual correction of false or misleading claims

He said there was a “real failure” to emphasise the local voices component of the proposed model, and pointed to discrepancies between media efforts that provided accurate information and those that, knowingly or not, amplified falsehoods.

“While some journalists to whom I spoke said ‘We’ve covered it already,’ it was blatantly obvious that one-off articles or interviews simply weren't sufficient. On the other hand, the conservative media working against the Voice recognised that constant reinforcing of misinformation was an effective tactic.”

Pakana said there was no “concerted strategy” to combat misinformation.

“Frankly, this influence should have been recognised much earlier and countered. I do believe that there are elements in the pro-Voice media who were either intimidated by anti-Voice media or silly enough to believe that ‘the electorate will know they’re lying’.

“The fact is that much of the electorate did not recognise misinformation and not nearly enough was done to call out those in the media for spreading that misinformation.”

Fact checkers need to establish trust with audiences and communicate using plain and accessible language

In an interview with CrossCheck, Luke Pearson, founder and CEO of the Indigenous media consultancy IndigenousX, shared some advice on how the media can improve its reporting, especially regarding the framing of Aboriginality.

Pearson said fact checkers could increase the impact of their work through communicating in a language that is accessible to audiences outside of academia and the media, providing greater context and nuance and building greater trust with the public.

“Explain it as you would explain it to a teenager, who doesn’t work in the space, to someone who is interested, but doesn’t have the training or the language. That’s what you need to do if you’re going to cut through to the public.”

He criticised objectivity in Voice reporting, saying that there is a degree of impartiality and critique required.

“A lot of media in the world and certainly in the academic space have abandoned the language of objectivity because we know it doesn’t exist. But truth, accuracy, impartiality, integrity, these are still important principles to strive for.”

“That’s one of the problems with the way the media engaged with the referendum. The media were fact checking elements of the campaign, they weren’t having enough conversations about racism in the country and the status of Indigenous people within it. It’s the campaigner’s job to campaign. It's the media’s job to have conversations.”

To build civic literacy skills, he raised the need for the media to provide more context, nuance and analysis in their reporting.

“Too many of us in the media see our role as sort of like the wizard, you know in The Wizard of Oz, we’re behind the screen doing the magic and just giving out the answer. We’re not pulling back the screen and showing the working out. Showing the problem, showing the complexity.”

Pearson said throughout the referendum campaign, the media tried to lean into a “deficit discourse”, portraying Indigenous Australians in terms of deficiencies and deviancies, while ignoring the broader context of systematic racism.

“No one was having that meaningful conversation about our humanity, our agency. About justice outside of charity.

“The self-determined right of Indigenous peoples is to determine for ourselves our own status within the country, to organise amongst ourselves to determine our relationship to the colony. Most people don't want to hear that, they don't want to talk about that, they don't want to think about that.”

He suggested that a more constructive approach the media reporting on the Voice could have adopted would be to focus on a framework based on strengths and rights.

“Our need for a voice, if you want to argue that we had one, is not so much based on disadvantage or disparity. It's a right to a voice based on our status as Indigenous peoples.

“You can strengthen the argument for that right by showing how it could combat disparity, but even if we attained equitable outcomes, we would still have a right to the Voice. We don't lose that right by virtue of attaining a level of equity.”

Building on this, he criticised the absence of racial literacy in the referendum campaign.

“You can’t have a practical civic literacy that ignores a history of systemic and systematic racism.

“So, understanding how the deck is stacked, generally understand, that it is stacked against us specifically.”

Pearson emphasised the need for fact checkers and journalists to be racially literate and to apply a cultural lens to their reporting: “It needs to be everyday business.”

Part 3: Inoculating the public against misinformation

It is not an isolated incident that Voice misinformation continued to travel online despite being debunked time and again. There are many theories as to why in general, misinformation is hard to correct once it is in the public mind.

CrossCheck spoke to Dr. Mathew Marques, a senior lecturer at La Trobe University who studies how attitudes are formed around socially contentious issues through the lens of social psychology. He said there were at least two observable behaviours sustaining the four narratives in the leadup to the referendum.

“The first is that some people perceive these as a realistic and symbolic threat. That is claims that individuals will be materially worse off, and that Australian cultural values will change.

“The second is that the claims are ambiguous, oversimplifications, and misrepresentations that either make them fit with pre-existing beliefs individuals may hold towards the Voice, or provide sufficient flexibility to create doubt and uncertainty for people around change, thus creating a greater inertia and a preference to maintain the status quo.”

So how can we avoid being influenced by incorrect information?

One answer is through inoculation theory, which in the case of misinformation means immunising the public against misleading information before it becomes viral.

Media should beware of amplifying potential misinformation

From a media communications perspective, Dr. Marques said there were two best practises for inoculating the public against misinformation:

“Media should avoid evocative headlines, and if reporting on outlandish claims then do so in a manner where it is clear to a reader there is little basis or support for such a claim. In topics where there is a risk of misinformation, then inoculating the public, by advising readers on the tropes and strategies used by agents of misinformation is helpful.”

He said understanding that emotional language and imagery that makes you feel angry or outraged is a tactic used to get your attention and increase the likelihood of spreading misinformation is important.

“Studies suggest that training individuals to identify strategies used in misinformation such as appeals to emotion, muddled arguments, or scapegoating have been shown to increase efficacy in accurately identifying misinformation.”

Fact checks can benefit from including more contextual information, including how misinformation was created and shared

A 2012 study found that for debiasing to be successful, an alternative explanation provided by the correction must be “plausible, account for the important causal qualities in the initial report, and, ideally, explain why the misinformation was thought to be correct in the first place”. Fact checks should explain the motivation behind an incorrect report and be tailored to the audience holding the worldview, the researchers stated.

CrossCheck reached out to Professor Sander van der Linden, a professor of social psychology in society and director of the Cambridge Social Decision-Making Lab, who provided useful tips for anticipating and preventing misleading information.

“Inoculation is actually perfectly suited for claims that are not easily debunked as true or false. The purpose of inoculation is often to empower people to spot the cues and tactics so that people can make up their own mind.”

There is a need for greater effort in inoculation and “prebunking” practices

He listed some common tactics used to spread misinformation, including the use of the polarising “us vs them” framing, the use of heavy emotional language to fearmonger and manipulate people, conspiracy theories, and breeding more extremist thinking through floating false dichotomies or scapegoating minority groups.

“You’d want to expose the logical fallacy or dubious claim through a weakened dose analogy in a way that resonates with people (e.g. through humour or animation or popular culture). Ideally the communicator is also someone people trust.

“You want to give people the skills to see through manipulation in a non-threatening way, ‘reveal the magician’s trick’ rather than focus too much on what is true or false all the time.”

Both Dr. Marques and Professor van der Linden said there is no such thing as overcorrection.

“We now know that concerns of a 'backfire effect' whereby repeating misinformation alongside a correction, does not increase belief in that misinformation.” Dr. Marques said, adding that “there's strong evidence of an illusory truth effect following repetition. That is, repeating information increases the belief that the information is true. This might also work for repeating correction claims.”

Conclusion

This research report found that Voice misinformation ran rife for several reasons: fact-checking efforts, while often quick-acting and consistent throughout the referendum cycle, had limited visibility online; a disjointed and delayed media response against misleading narratives; and seemingly low media literacy abilities among social media users to discern referendum mis- and disinformation.

Based on our findings and expert advice as noted in this report, here are five recommendations for journalists and fact checkers to mitigate disinformation more effectively:

- Fact checkers need to establish trust with audiences by communicating in a way that is accessible to people outside of academia and media.

- More collaboration is needed between fact-checking and media organisations in order to increase the exposure of corrective information.

- Media should beware of amplifying potential misinformation by avoiding evocative headlines and alerting the reader if claims have little basis and support.

- Fact checks can benefit from including more context, such as why a piece of misinformation was initially thought to be correct, as well as highlighting the tactics used to create and share the misinformation.

- Greater efforts in inoculation and “prebunking” practices through articles that empower the public to learn misleading techniques and tactics, and thus becoming less susceptible to potential misinformation.

This report illustrated how “bothsidesism” reporting seriously undermines context. Prebunks can get an early reading on the full context of a situation and can help to reduce the risks associated with false balance reporting.

Areas where misinformation can be expected include historical aspects, potential wedge issues as well as areas where one can expect an insufficient supply of quality information to meet the demand, especially in times of fear or confusion. These early observations can form the basis of prebunks and inoculation work, which can help audiences recognise potential misleading information and the tactics used to spread it. An example of that is the fear tactics used to promote the narrative that the Voice would lead to “reparations” or a change in native title law or land rights.

CrossCheck prepared these prebunks early in the referendum cycle and shared them with our media partners. The list was built upon over time as online chatter grew after high profile voices boosted misinformation. The prebunks were often echoed by fact checks and academic articles highlighting the same false or misleading claims.

As this research shows, fact checks and prebunk materials can be further leveraged by media coverage that references the work. Media reports provide further reach and utilisation of fact checking and prebunking work, which is often labour intensive. This also makes the case for stakeholders — from governments and regulators to tech platforms, researchers and industry — to further investigate and explore potential mechanisms to enhance the reach of this information.

Trusted messengers — be they the media, communicators or those with influence in communities — need such mechanisms where they can continuously warn the public of what to expect, and what information is evidence-based. As noted by Charles Pakana, “one-off” reports are simply not enough.

Related News

Acknowledgement of Country

RMIT University acknowledges the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nation on whose unceded lands we conduct the business of the University. RMIT University respectfully acknowledges their Ancestors and Elders, past and present. RMIT also acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and their Ancestors of the lands and waters across Australia where we conduct our business - Artwork 'Sentient' by Hollie Johnson, Gunaikurnai and Monero Ngarigo.

More information