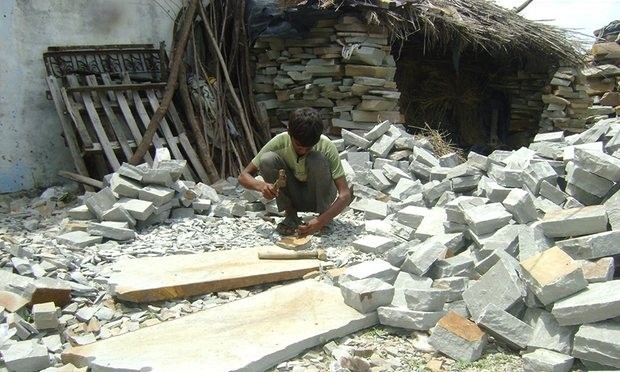

The Modern Slavery Act aims to combat bonded labour. Will it help these workers?

The UK is the major buyer of Rajasthan’s stone, and Australia is in the top 10 buyers. So surely, an ethical burden falls on these countries to address the conditions of work in Rajasthan’s stone quarries. Both Australia and the UK have enacted Modern Slavery Acts. Neither cover child labour or egregious occupational injury or illness such as silicosis. But both aim to address bonded labour which is common in Rajasthan’s quarries.

These Acts are known as ‘disclosure-based regimes’. Under these Modern Slavery Acts companies of a certain size must report on their efforts to assess risks of modern slavery in their operations and supply chains, and their efforts to eliminate and remedy it. However, there are no penalties for firms for not reporting or acting on these risks. Disclosure-based regimes are based on the idea that large firms will want to report on and act to address modern slavery in order to protect themselves from reputational damage.

Our research shows that disclosure-based regimes are unlikely to make much difference for quarry workers in Rajasthan. The primary reason is because of the nature of the sandstone supply chains. Unlike, say, a garment supply chain with lead firms like ‘H&M’ or ‘Nike’, the stone industry lacks major players with the power to shape production conditions.

It is mainly larger construction firms in the UK and Australia that report under the Modern Slavery Acts. Stone importers and retailers in these countries are not large enough players to be captured by the legislation, in general, and exporters and stone processors in India are unlikely to be recruited, even indirectly, by such regulation. Though large volumes of stone are exported, there are no major buyers against whom leverage can be applied to bring about change within supply chains.

Furthermore, the supply chains are difficult to trace. It makes it difficult for businesses like construction firms to assess the risk that stone has been imported from Rajasthan and is linked to egregious human rights breaches. One representative of a multi-stakeholder initiative interviewed for our study noted the particular difficulties in attempting to map the supply chain in Rajasthan’s stone sector:

It’s so complex in the sense of you’ll get to your exporter or processor and then they could be buying for a number of businesses. It’s a very informal structure for buying stone, so it can just see somebody going to market and looking for a particular colour … there’s very little trail in terms of actual documentation and people recording it of where the extraction quarry may be (Member of multi-stakeholder initiative, interview, 21 October 2013).

These factors all combine to create significant barriers for a construction firm to trace the supply chain or enrol supply chain actors to bring about change.

So . . . are Australia and the UK off the ethical hook?

We don’t think they should be. While the Modern Slavery Acts may not make much difference, there are many ways that countries in the Economic-North can help workers in the Economic-South.

Trade unions and worker groups that are working to improve the lives of workers who toil in Rajasthan’s mines deserve support. The peasant movement that occupied New Delhi’s streets earlier this year also addresses the root causes of Rajasthan’s bonded labour. Workers become indebted after farming becomes untenable due to poor market conditions, drought, and other forces that the peasant movement is fighting to address.

Rajasthan’s state labour inspectorate is trying, also, to address working conditions with very little resources, and the state Human Rights Commission has set up a major scheme providing compensation to victims of silicosis.

And though controversial, trade preferences that reward the stone industry for improving labour conditions would likely do a great deal more to change the Indian stone industry than the Modern Slavery Act.

Authors: Associate Professor Shelley Marshall and Sara Todt

Associate Professor Shelley Marshall is Director of RMIT University's Business and Human Rights Centre. She has worked in the field of corporate accountability for 30 years, first as a lawyer and practitioner, and subsequently as an academic.

Sara Todt is a PhD Candidate with RMIT's Business and Human Rights Centre. Her research concerns workers in complex supply chains.