Ray Kurzweil’s widely publicised vision of an imminent “technological singularity,” where human intelligence fuses with AI, is emblematic of this sentiment. Predictions such as Elon Musk’s recent claim that AI will replace “all desk jobs” only reinforce the view that we are hurtling toward an age of exponential, self-reinforcing innovation.

But economic growth has never been about optimism alone. Societies advance when they discover genuinely new ways of doing more with the same, or fewer, resources. Without such breakthroughs, economies run headlong into diminishing returns - we add more labour, more capital, more effort, yet gain progressively less. In a world facing tightening resource constraints, from ageing populations to environmental limits, the need for transformative technologies has never been greater. AI is often invoked as the technology that might finally break through these limits.

Yet a growing body of economic and scientific evidence paints a more sobering picture. Far from accelerating, the rate of transformational technological progress appears to be slowing, and in some areas, stalling altogether.

Productivity Growth Has Fallen, Not Risen

The most important long-run indicator of technological progress, labour productivity growth, has been trending down for decades. Between 1990 and 2005, Australia’s labour productivity grew by an average of 2.2% a year. From 2005 to 2025, that figure fell to just 0.9%. The United States exhibits a similar pattern, with productivity growth declining from 2.1% to 1.4% over the same periods.

These figures matter. Technology is the principal engine of productivity growth, and productivity growth is the foundation of rising real wages, living standards, and long-term economic welfare. When productivity slows, it signals that the underlying rate of technological progress may be slowing with it, and that the assumptions underpinning current narratives of exponential technological advance warrant closer scrutiny.

Innovation Is Getting Harder Everywhere

Emerging academic work supports this conclusion. A landmark 2020 American Economic Review study examined multiple frontier technological fields: semiconductors, agriculture, biotechnology, and medical technology. The authors found that producing a given level of scientific or technological output now requires dramatically more researchers and R&D spending than it once did. In other words, research productivity is falling. The implication is that breakthrough innovation, the kind that allows society to escape diminishing returns, is becoming rarer.

Measuring innovation, however, is inherently challenging. Ideas are intangible and do not scale linearly: two ideas are not necessarily “twice as good” as one. Patents, publications, and R&D budgets offer only partial and imperfect proxies. Major breakthroughs often emerge from a series of incremental developments rather than a single, easily identifiable moment. Compounding this, the information embedded in patent or scientific documents is qualitative and context-dependent, making it difficult to assess the true novelty or technological depth of any individual invention.

But advances in artificial intelligence give us new tools to grapple with this problem.

Using AI to Measure Innovation More Accurately

At RMIT’s Finance and Technological Innovation research cluster, we use modern natural-language processing models to analyse every US patent from 1969 to 2024—more than 11 million in total. Rather than simply counting patents, we extract meaning from the text of each invention to classify them as:

- Radical: genuinely novel technological advances

- Pioneering: inventions that introduce new terminology or concepts later widely adopted

- Routine: incremental improvements

- Redundant: filings that contribute little new knowledge

This allows us to track not just the volume of innovation, but the quality and transformational potential of inventions over time.

What the Data Shows: More Inventions, Fewer Breakthroughs

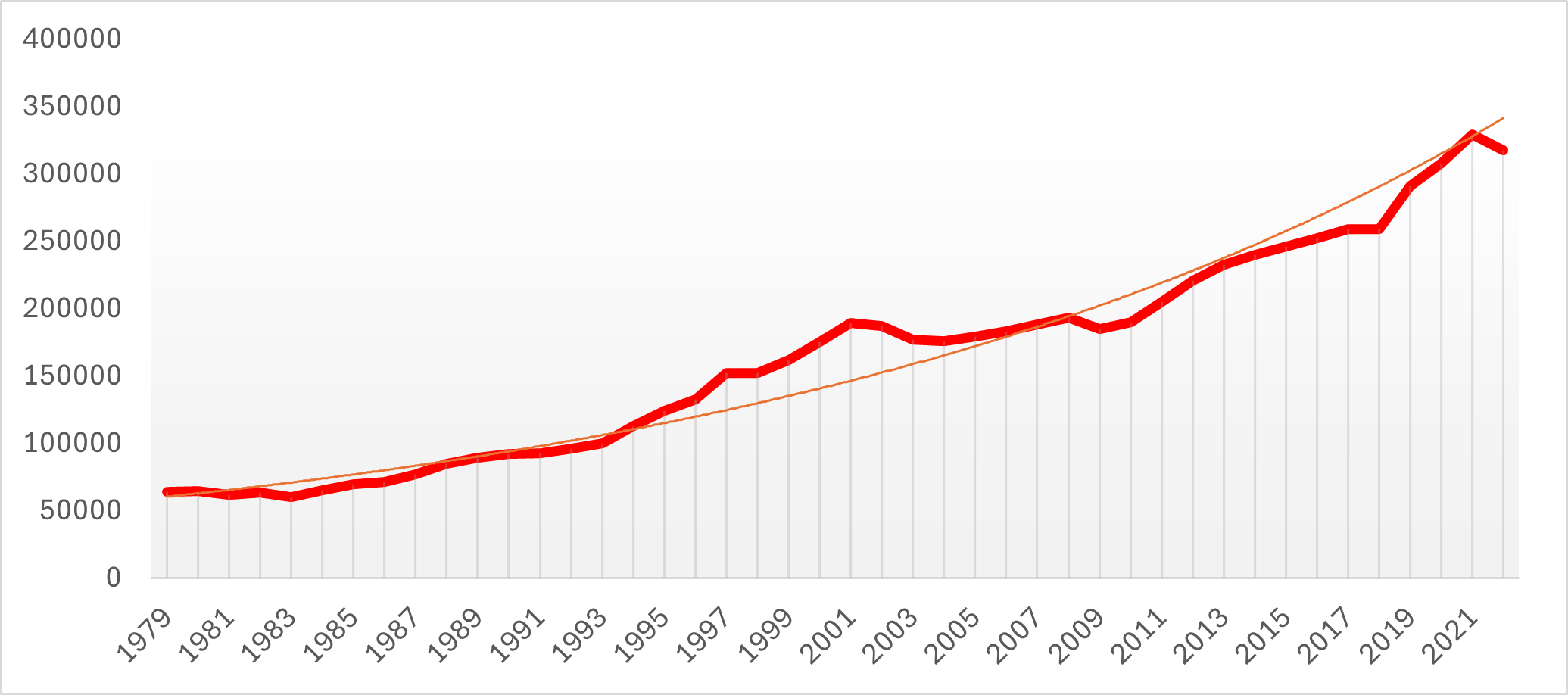

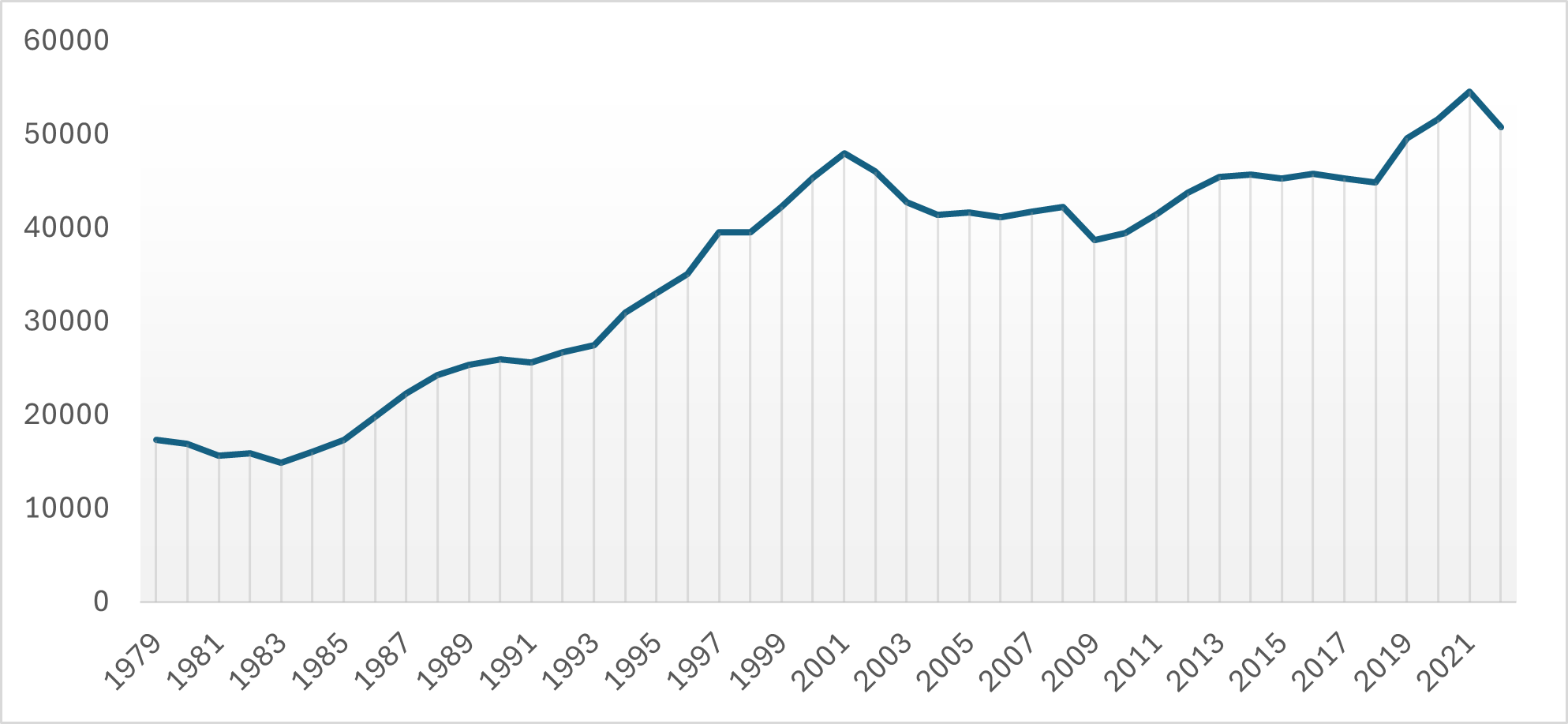

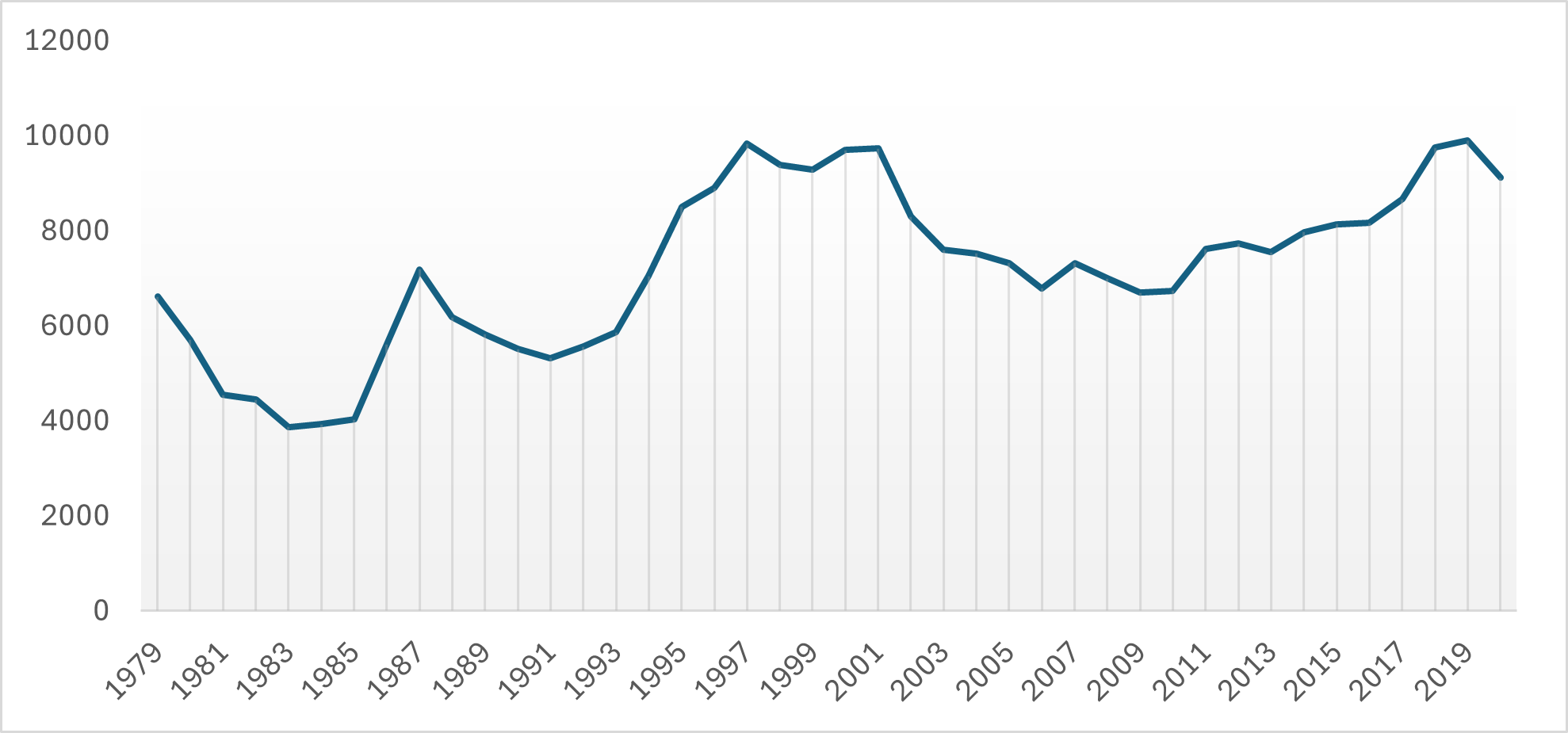

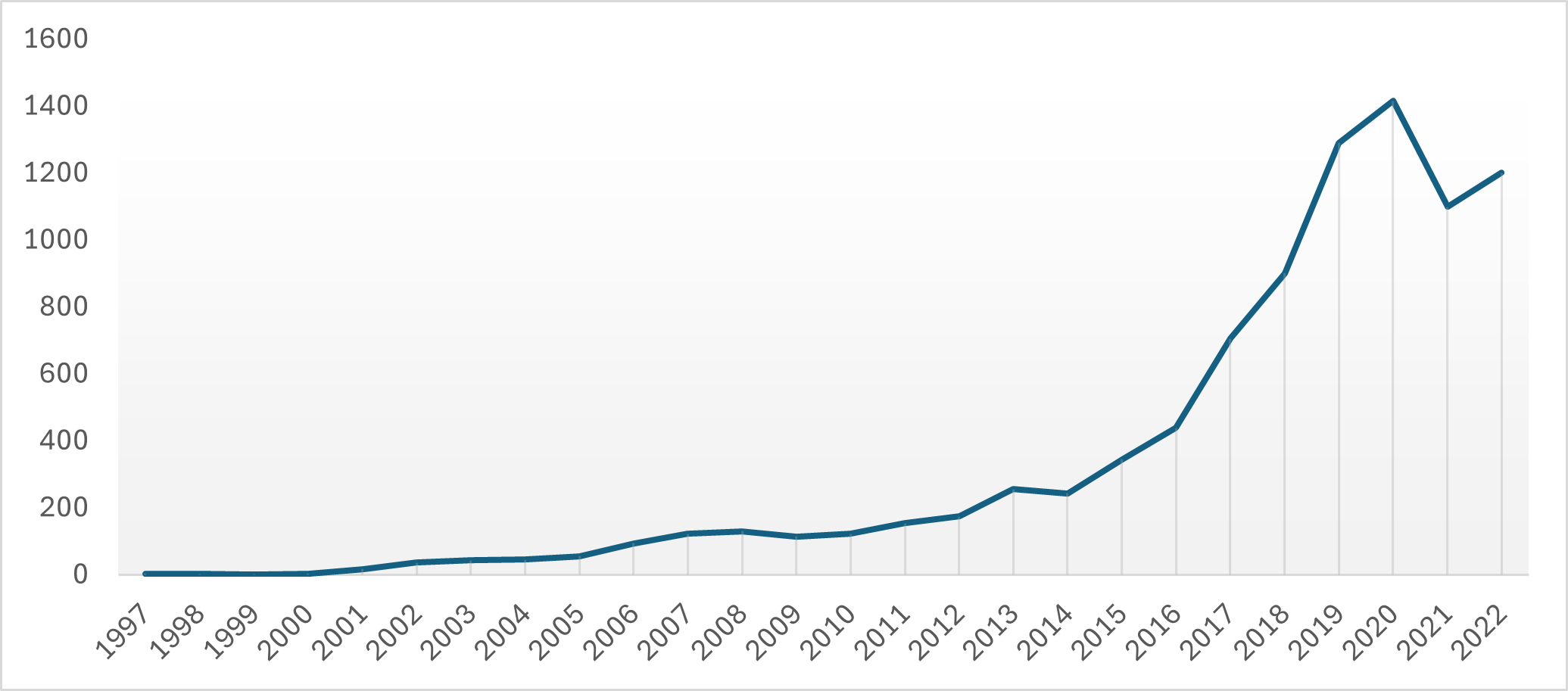

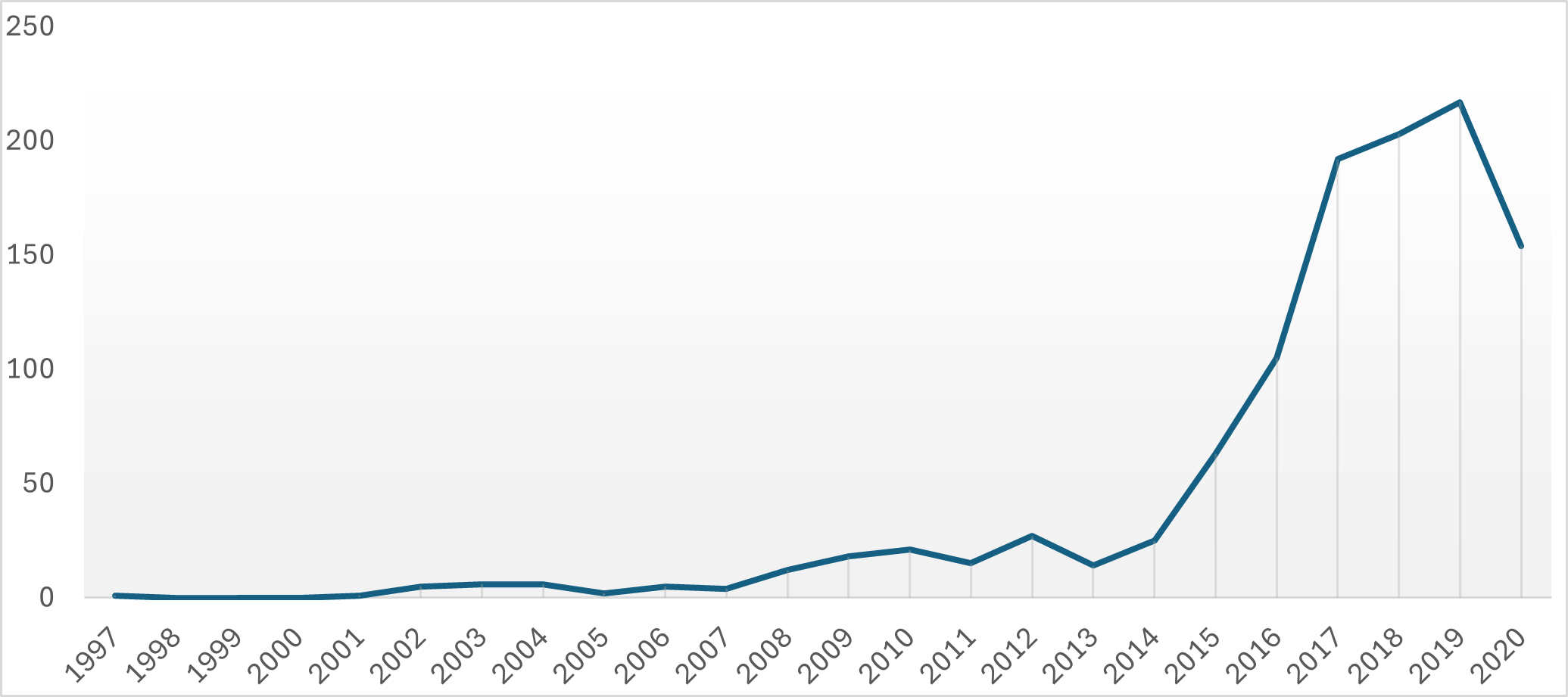

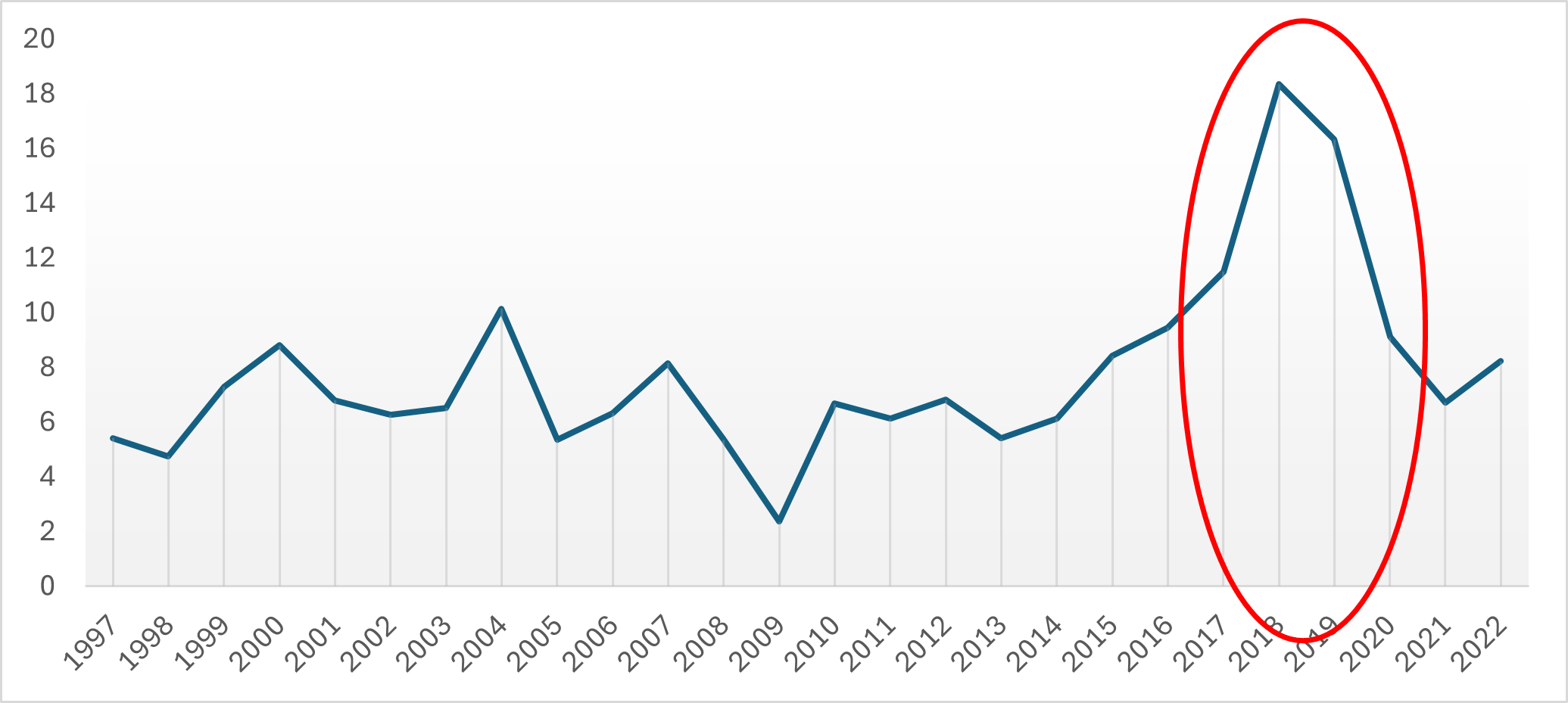

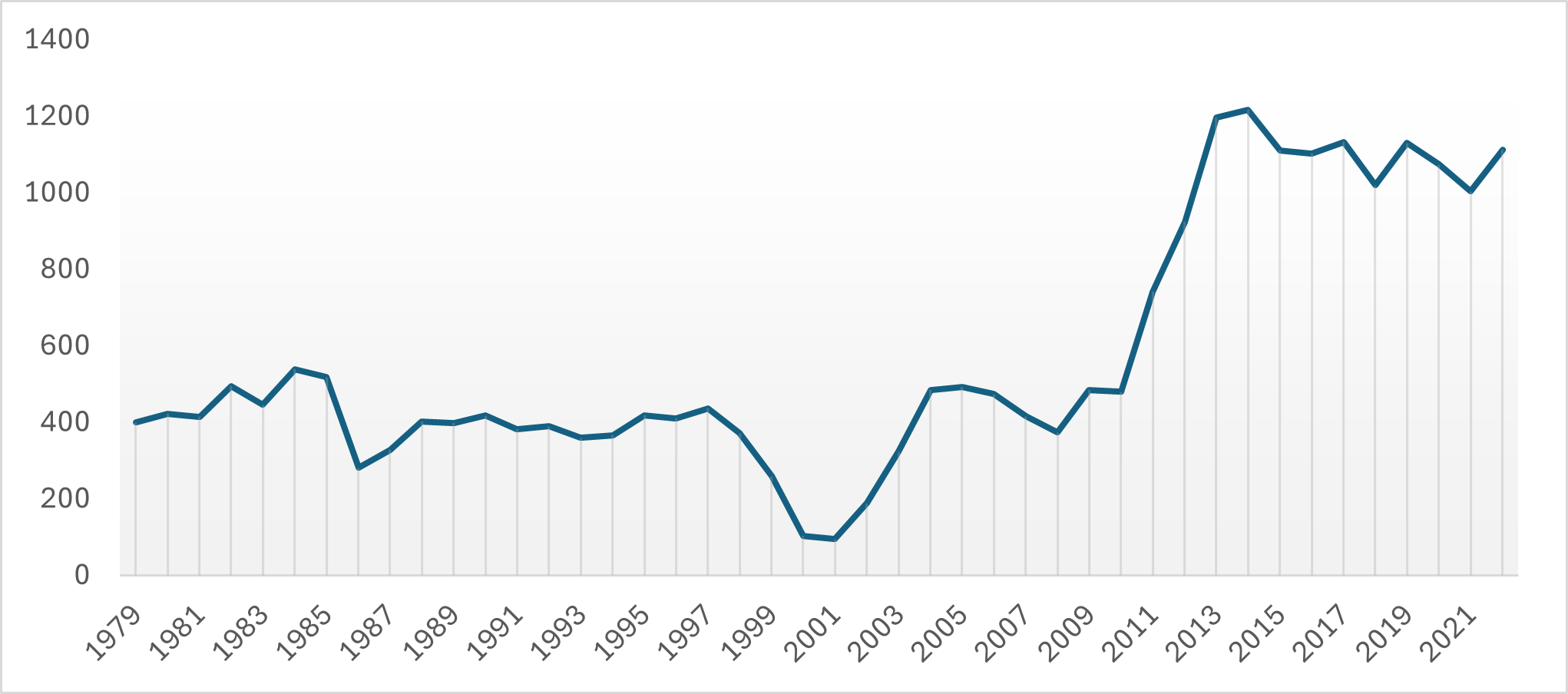

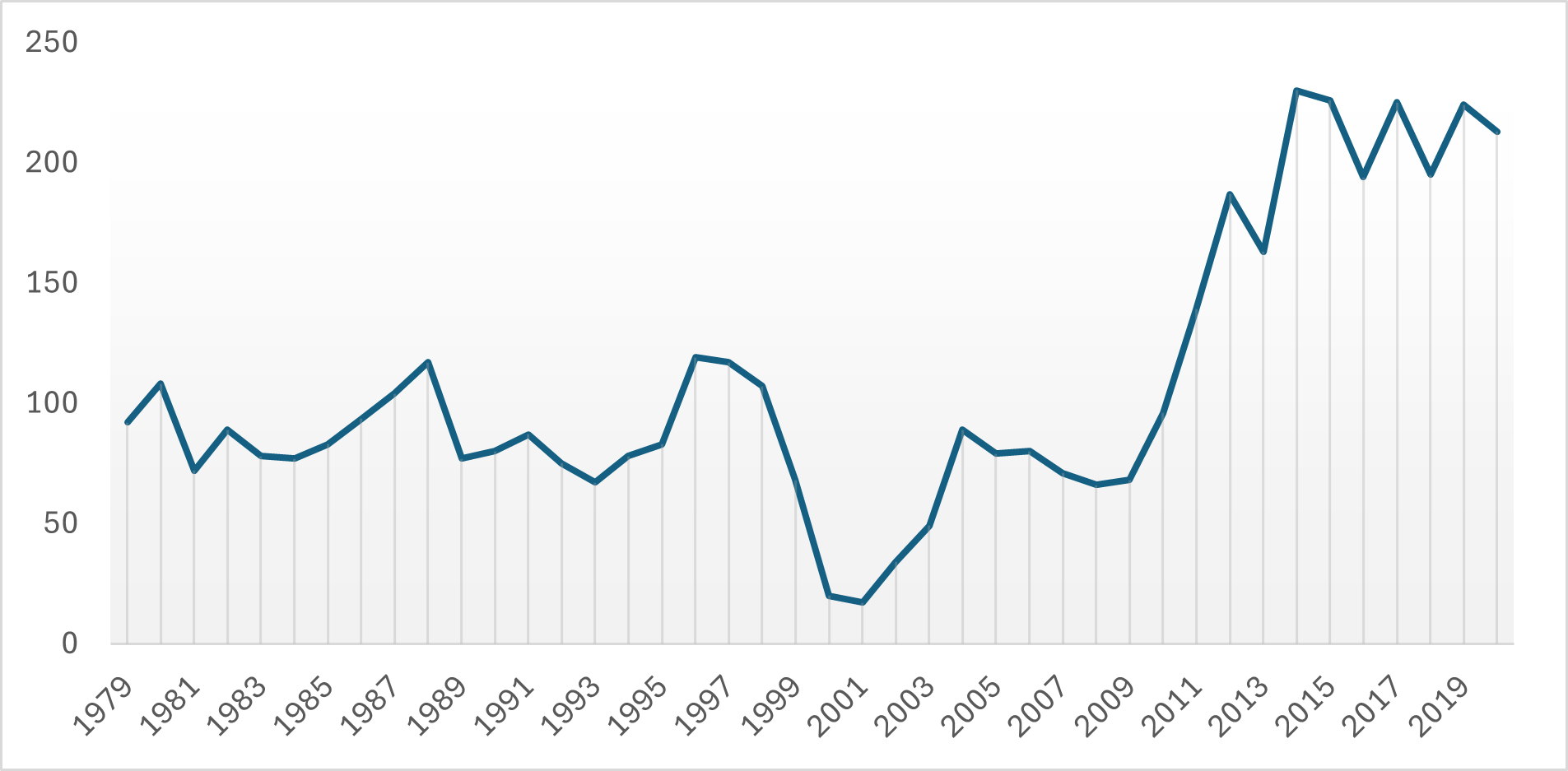

The raw number of patented inventions has grown exponentially (Figure 1). But once we isolate radical and pioneering innovations, the ones that drive productivity shifts, the picture changes dramatically.