Its “approach to market” strategy has effectively asked companies how much government money they need to do so. But even with subsidies, this plan will take years.

So why can’t Australia make the mRNA vaccines?

That’s not actually the right question to ask. The crucial issue is why Australia hasn’t been producing the type of companies that can make mRNA vaccines. Why don’t we produce more start-ups like BioNTech or Moderna – the two companies that developed and brought the mRNA vaccines to market?

Answering this question is important not just to vaccines but to the whole range of “deep technologies” that will shape economic development and sustainability in the 21st century.

What is deep technology

Technology is generally defined as the application of new knowledge for practical purposes. Deep technology is slightly different. It refers to the type of organisation required to bring certain types of technological innovation to fruition.

It is more accurate to talk about deep technology ventures. BioNTech and Moderna are two such examples. Both are relatively young companies — BioNTech was founded in Germany in 2008, Moderna in the US in 2010 — that have brought to market a technological solution underpinned by substantive advances in scientific research, engineering and design.

Deep-tech ventures span advanced materials, artificial intelligence, biotechnology, blockchains, robotics and quantum computing. A few are now household names, such as Tesla and SpaceX, but most fly under the radar of public awareness, as Moderna and BioNTech did before the pandemic.

They include synthetic biology companies such as the Ginkgo Bioworks and Zymergen, which can program organisms to create completely new biologically based materials for use in manufacturing. These “biofoundries” can produce everything from biodegradable plastics, new protein-based foods to probiotic microorganims that improve human health.

There are advanced engineering companies such as Carbon Engineering and Climeworks, working on ways to suck carbon dioxide from the air to use for industrial purposes.

There are experimental energy companies such as Commonwealth Fusion Systems and Helion, which are working on making the holy grail of clean energy technology, nuclear fusion, a reality.

Australia’s problem with deep tech

Australia’s problem with deep technology ventures isn’t to do with the quality of our science and research. We produce, per capita, nearly twice as many scientific research papers as the OECD average.

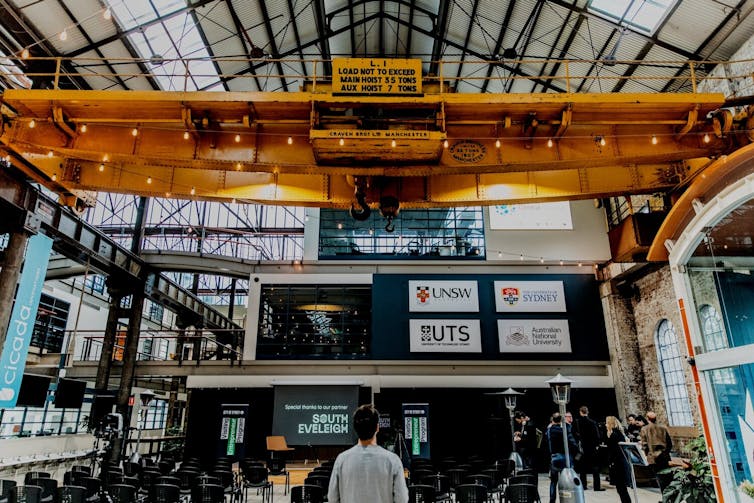

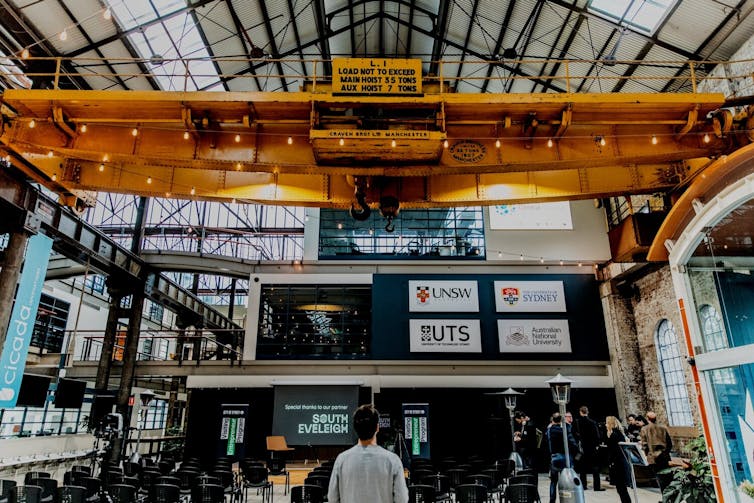

We also have some great support structures, such as the CSIRO, the national research and science agency, and Cicada Innovations, the deep-tech venture incubator in Sydney.

The Cicada Innovations deep technology incubator, in the former Eveleigh Railway Workshops in Redern. Kitti Gould/Cicada Innovations

The problem is our inability to take our scientists’ knowledge and turn it into innovative ventures. Other countries are much more successful at this. Britain, Germany and France, for example, all publish fewer research papers than Australia per capita but produce far more patent applications — a key indicator of potential research commercialisation. The US produces nine times as many per capita.

The ‘valley of death’

Australia’s primary challenges here are related to the culture of innovation and entrepreneurship and our current mechanisms for long-term venture funding.

Deep-tech ventures usually require longer time horizons to translate new scientific insights into commercially successful products. Few universities are set up to see this process through. Public funding mechanisms prioritise basic research leading to publications, not the entrepreneurial processes required to find a market fit for a new product or solution.

Nor are venture capital funds — the normal providers of seed funding — well placed to fund deep technology ventures. This is partly because the science itself can be difficult to understand. Also many funds prioritise ventures that can “exit” through an acquisition or public offering within 10 years.

The complex science and length of time needed to commercialise deep tech mean many good ideas die in the so-called “valley of death” — the gap between initial seed funding and sustainable revenue generated from product sales. This gap is filled in some countries by investments from sovereign wealth funds, more “mission” oriented government programs and even prizes. Australia has yet to emulate these solutions.

These issues help explain why Australia’s investment in R&D as a portion of GDP over the past decade has declined, from a peak of 2.3% in 2008 to 1.8% in 2019. That puts us below the OECD average (2.47% in 2019), well behind innovation leaders such as Israel (4.9%), South Korea (4.6%) and Taiwan (3.5%).

In 2020 only 12 Australian companies were listed among the world’s top 2,500 R&D leaders (as ranked by EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard). This compares with Taiwan (88), South Korea (59) Switzerland (58), Canada (30) and Israel (22).

What can we do about it?

Australia’s future economic prosperity depends on our ability to translate scientific advances into innovation and entrepreneurship. Technological innovation is the only driver of economic growth over the long term. MIT professor Robert Solow won the 1987 Nobel Prize in Economics for his work demonstrating this point.

To correct our trajectory requires more “patient” capital. We are one of the world’s wealthiest nations on a per capita basis, but too much wealth is locked up in property ($8 trillion) and superannuation funds ($3.8 trillion) opting for “safer” investments.

If just 0.1% of superannuation assets were allocated to fund deep technology ventures, Australia would have a fund about as large as the nation’s entire current venture capital pool invested in the past financial year.

We also need leadership around a shared vision of the benefits of deep technology entrepreneurship. Not enough Australians recognise the importance of science and technology in driving both economic prosperity and addressing global challenges. Some are even suspicious that technology causes more problems than it solves.

But these ventures will be crucial to addressing pressing development and sustainability challenges, including climate change.

Tomorrow’s economy and society will be built with today’s scientific breakthroughs in deep technology ventures.

Author:

Julian Waters-Lynch - Lecturer Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Organisational Design, RMIT University

This article was originally published in The Conversation