RMIT University ethics expert, Associate Professor Eva Tsahuridu, says Australians had so far responded well to physical distancing orders in an attempt to slow the spread of coronavirus.

But sustaining high levels of compliance as time drags on could be increasingly difficult, she warns, especially among younger people less motivated by fear for their own health.

“If you want to keep convincing people that physical distancing is the right thing to do – the ethical behaviour we want to comply with - messaging needs to target both our hearts and our minds,” she says.

Tsahuridu says public health information could either improve or impede our ability to see coronavirus as an ethical issue, and whether we decide to do what is right or not.

“While graphs and percentage figures are useful in explaining the importance of physical distancing to slow the spread and protect the most vulnerable in our community, it will miss the mark with many people,” she says.

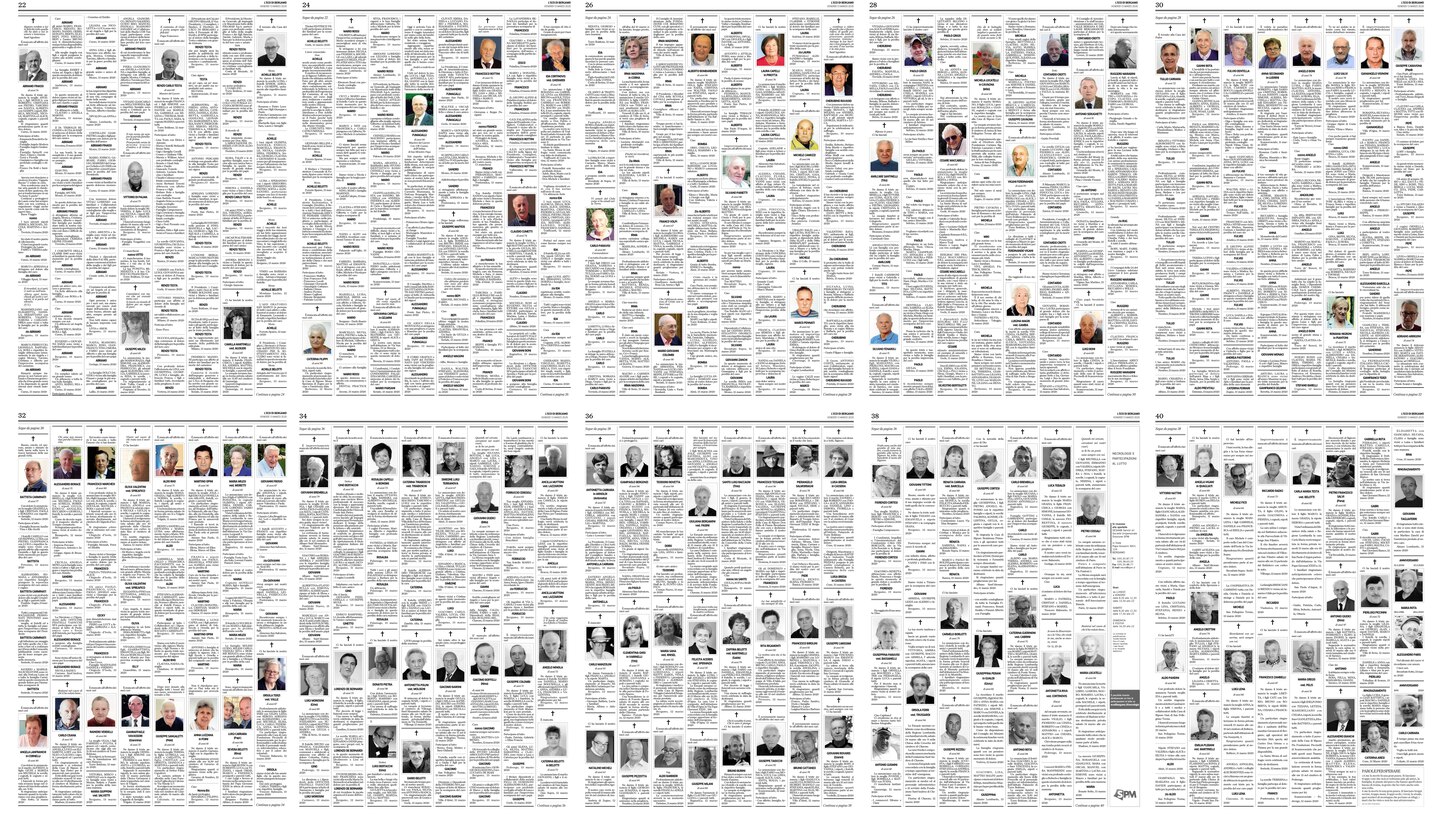

“The motto of ‘flattening the curve’ does little to emphasise the potential human suffering at stake. Neither does talking of people as ‘cases’.”

Tsahuridu suggests a more personal, story-driven approach may be needed in the months ahead.

“Allowing us to 'see' the people our actions endanger or even to 'interact’ with them via interviews will have much more impact on our behaviour,” she says.

These types of campaigns could be useful in helping lower-risk people understand that their behaviour - if they decide to disregard physical distancing orders - could lead to hundreds of infections and the deaths of people who have names, faces and loved ones that will miss them dearly.