The most advanced of these trials is in Brazil.

The timing of results will partly depend on how quickly volunteers are enrolled into the study, and the extent to which they are then naturally exposed to the virus in the community.

Hence trials need to be big and be in countries where the disease is prevalent.

We should know by the end of this year if the vaccine is a success. If it’s found to be safe and protective it can then be licensed.

What are the risks?

Australia’s agreement, signed with AstraZeneca, is a letter of intent, so the deal will only go ahead if the current phase 3 trials show the vaccine does indeed protect against COVID-19.

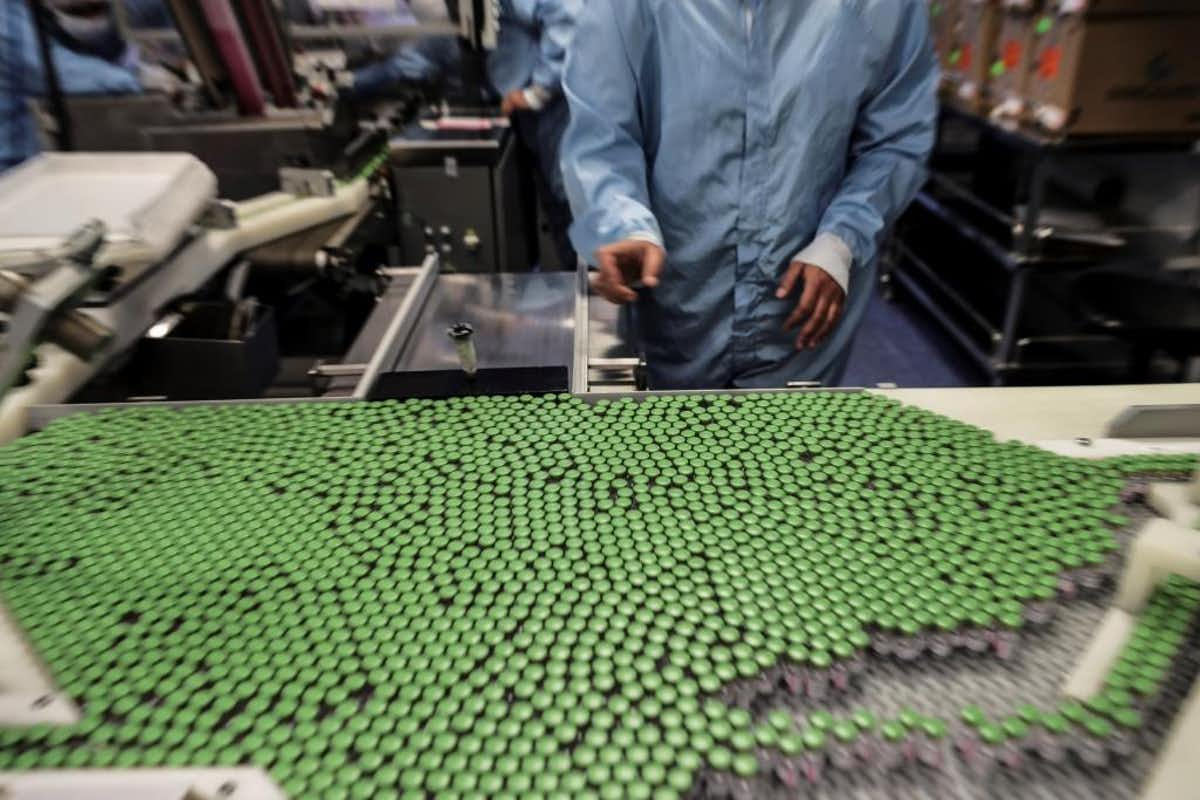

If it does, Australia will receive the vaccine’s formula and permission to manufacture it on shore.

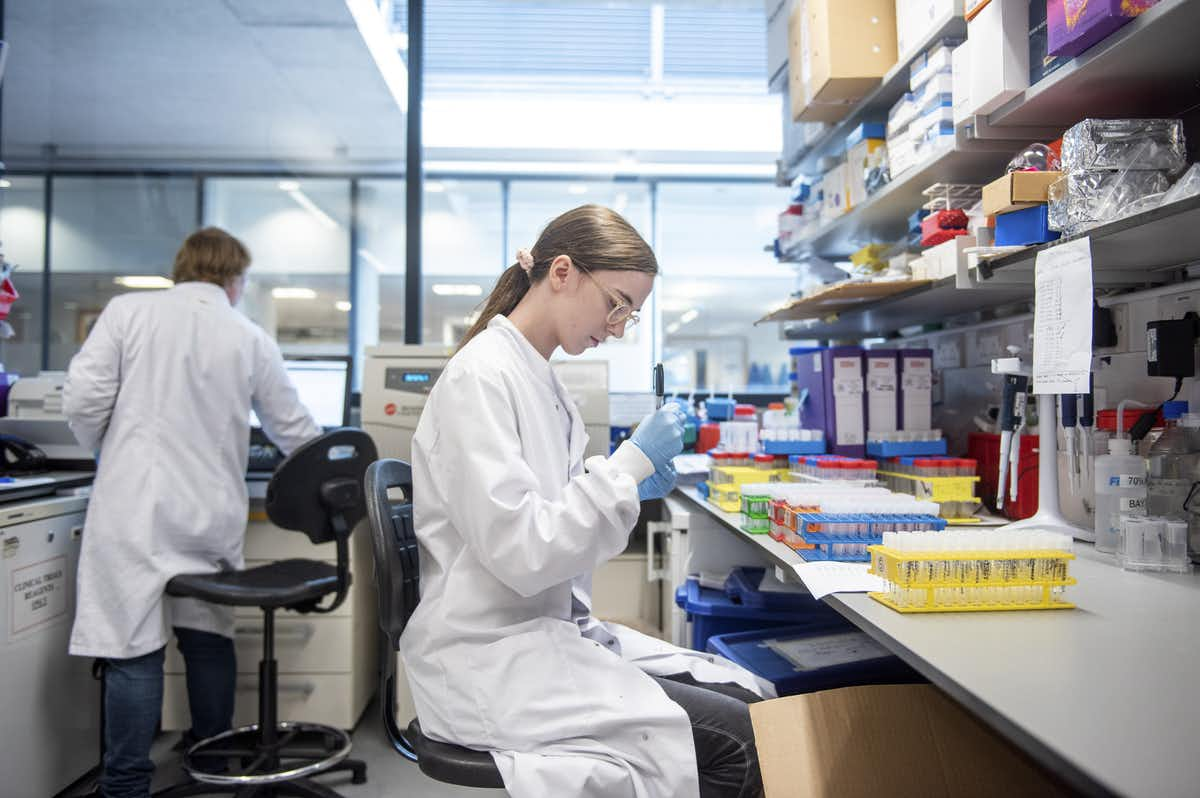

Biotechnology company CSL in Melbourne has had discussions about potentially fully or partially producing the vaccine on shore.

Australia has also struck a deal with US medical technology company Becton Dickinson to supply enough needles and syringes to deliver the vaccine.

The government has pledged to provide the vaccine for free to all Australians.

All the signs are promising thus far, but there’s a risk at this stage the vaccine may not protect fully against COVID-19 in humans.

Indeed, most new candidate vaccines do not work during the development and testing phases.

However, as there are more than 160 different SARS-CoV-2 candidate vaccines based on diverse technologies in development, with 29 in clinical trials, it’s likely some will successfully make it through the pipeline.

There are several other candidate vaccines being tested in Australia, including at the University of Queensland.

The Australian government has also invested in its development financially, though no supply deal has been announced as yet.

It’s also important to note that even after phase 3 trials in thousands of people, some vulnerable groups may not respond in the same way to the vaccine as the healthy young adults mostly tested in these trials.

Encouragingly, the current phase 3 trials will include some older adults, but other vulnerable people may still require additional tests.

It’s great the Australian government is moving forward with this, but we must also remember the world’s poorer countries, and avoid the temptation to indulge in “vaccine nationalism” – rich countries monopolising vaccine stocks at the expense of others.

With this in mind, the COVAX global vaccines facility has been created by the World Health Organisation, global vaccine alliance GAVI, and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations.

This is an unprecedented global collaboration combining funds from wealthier countries to provide vaccines for low- and middle-income countries throughout the world.

And thankfully, Australia has made an in-principle commitment to join.