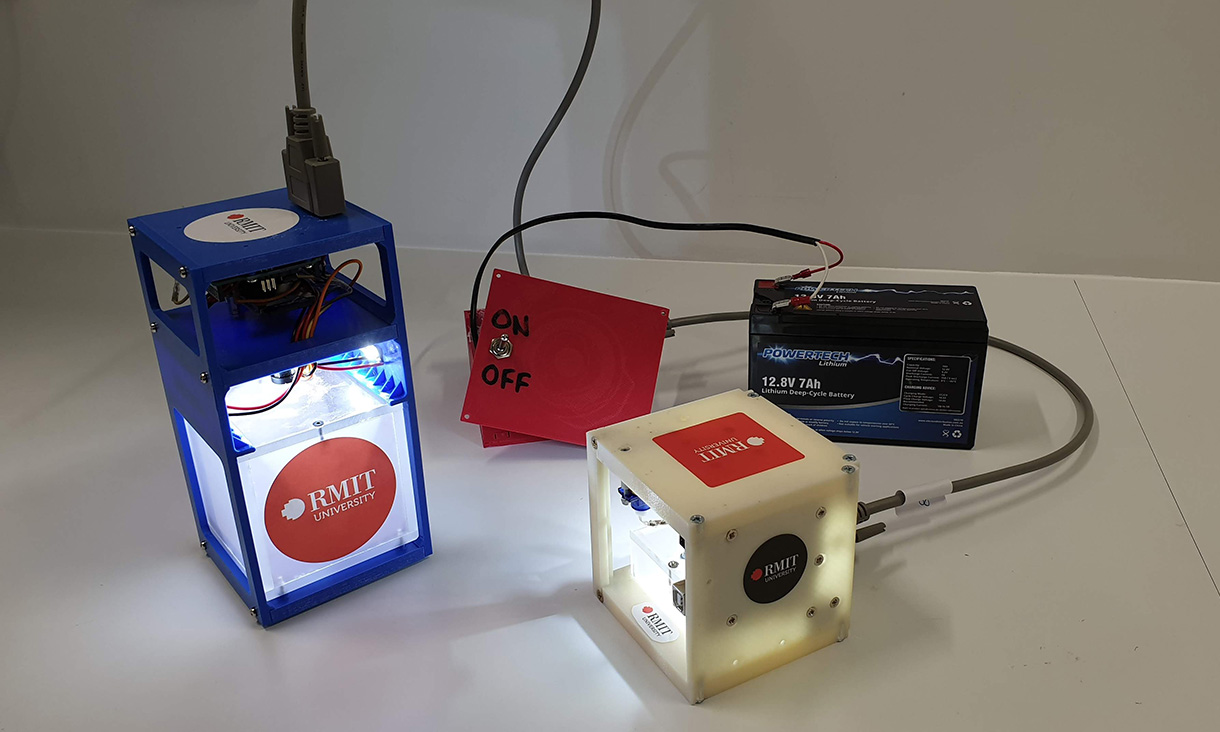

Rocket test proves bacteria survive space launch and re-entry unharmed

A world-first study has proven microbes essential for human health can survive the extreme forces of space launch.

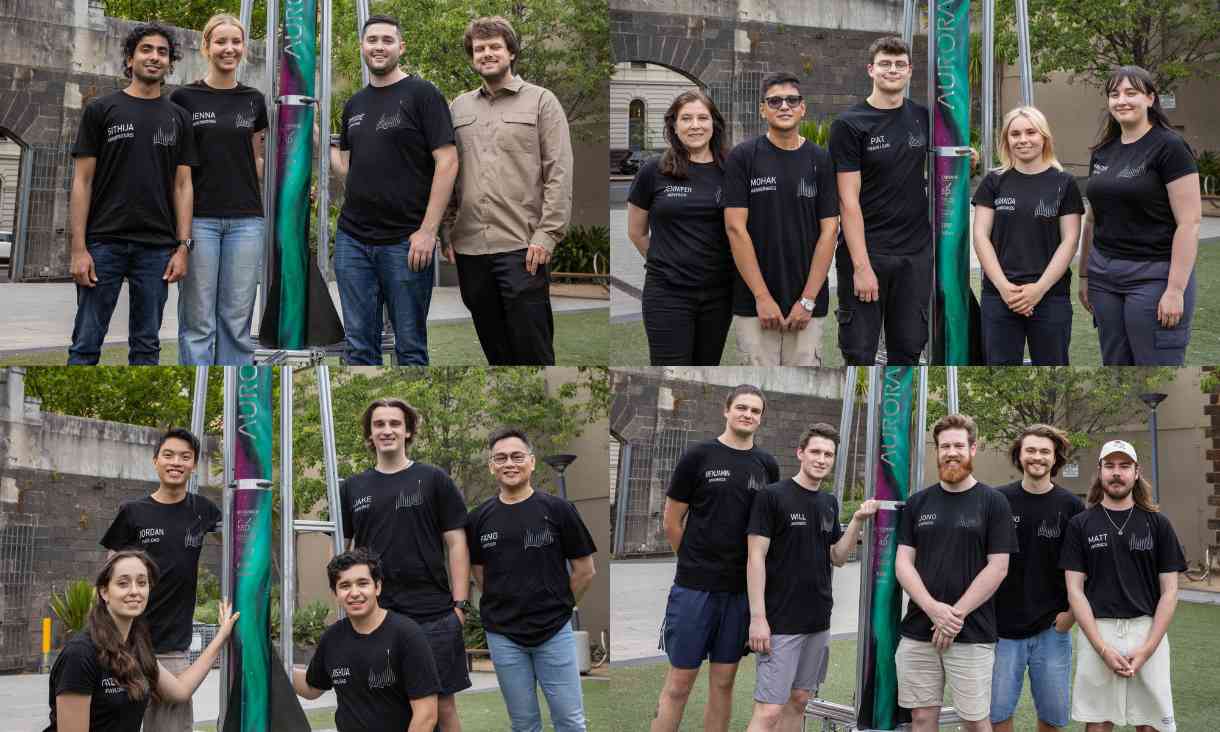

RMIT team wins Technical Excellence award at national competition

RMIT's student-led rocket team have continued their legacy of success at the Australian Universities Rocket Competition (AURC), placing second overall and winning the Technical Excellence Award for their design.

Applications open for RMIT and Leidos aviation scholarship

RMIT will again partner with Leidos Australia to offer scholarships to students completing an aviation degree in 2025.

Steady flight of kestrels could help aerial safety soar

A joint study by RMIT and the University of Bristol has revealed secrets to the remarkably steady flight of kestrels that could inform future drone design and flight control strategies.