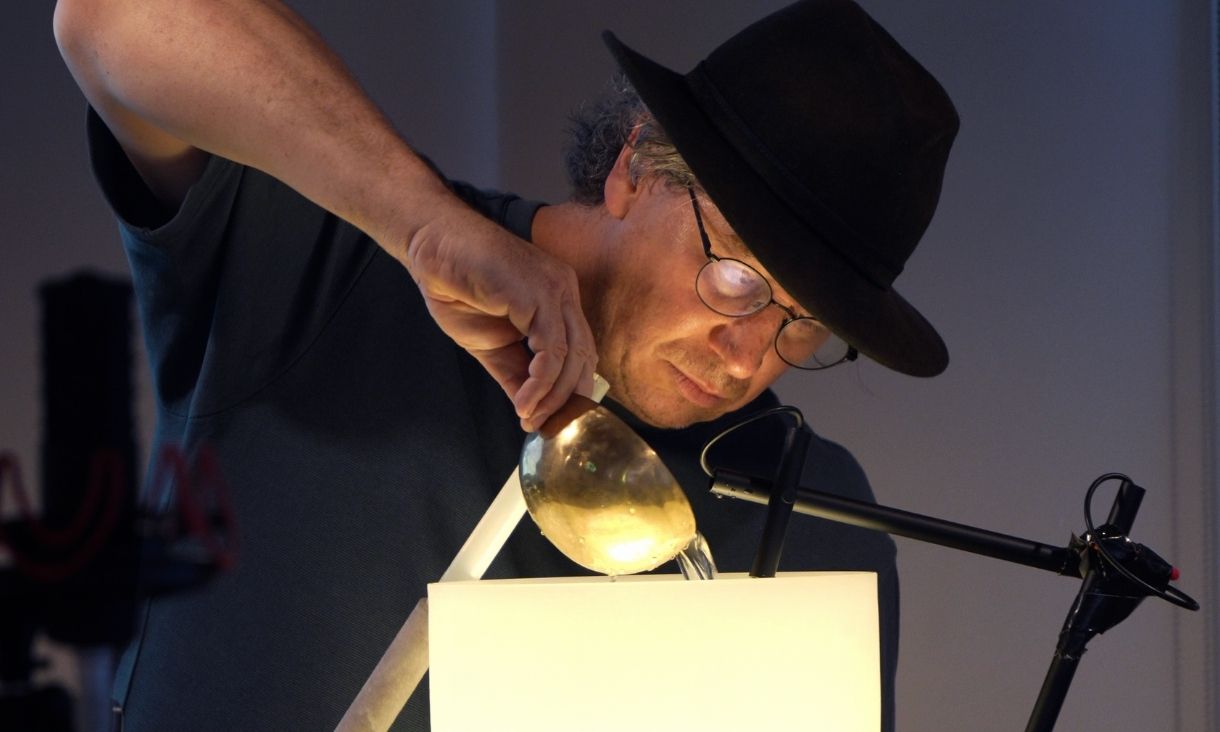

Creative Antarctica: artists transport audiences to the edge of the world

RMIT Galleries' latest - and one of its largest ever - exhibitions, Creative Antarctica: Australian Artists and Writers in the Far South, brings audiences on a journey to the Far South, offering new perspectives, encounters and understandings of one of the world’s most remote and fragile landscapes.

‘Incredibly resilient’ nylon device creates electricity under tonnes of pressure

RMIT University researchers have developed a flexible nylon-film device that generates electricity from compression and keeps working even after being run over by a car multiple times, opening the door to self-powered sensors on our roads and other electronic devices.

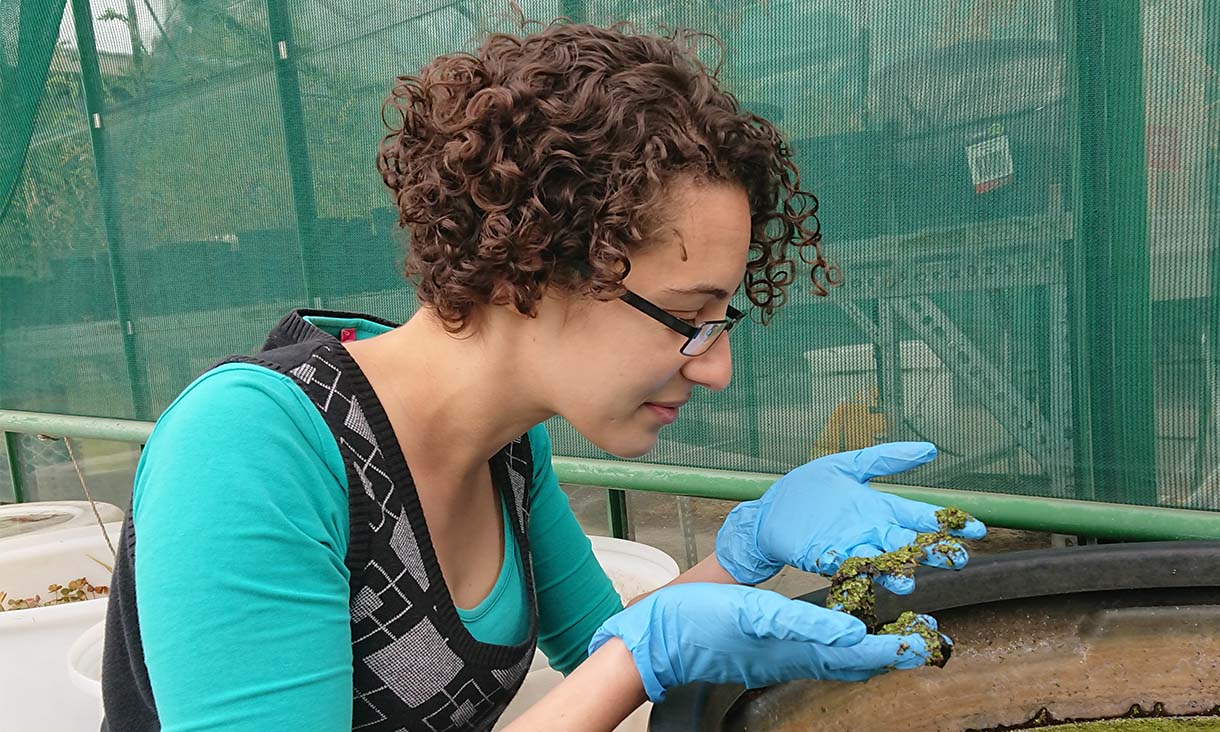

Indigenous plant could have handy health benefits

New research suggests an Australian desert plant could help food manufacturers improve protein quality and reduce reliance on added salt in staple foods.

Gathering of Cultural Custodians and international academics call for paradigm shift in land-based relationships

An RMIT-led event at CERES Community Environmental Park convened philosophers, artists, educators and Cultural Custodians to collectively reimagine regenerative relationships with land and place.