Both the EU & UK have compromised from their original positions in negotiating The Windsor Framework. Eliciting the EU’s core interest in assuring the integrity and protection of its single market, Brussels has unequivocally made their greatest concession on the movement of goods into NI. The EU’s former position insisted on its rules-based approach and continued implementation of EU regulations in NI. Under the new framework, however, the EU has accepted regulations that are more risk-based and proportional, working under the theory that the final destination of goods determines the risk level; thus, goods remaining in NI can be treated differently to goods entering the single market. Subsequently, Brussels secured its stipulation that the ECJ maintain its final arbiter jurisdiction over EU rules applying to NI under the protocol. The EU has also ensured that robust safeguards are in place around these new arrangements to help foster trust in the UK’s ability to enforce delicate border arrangements that control the flow of goods into its single market. Such safeguards allow the European Commission to increase inspections should the UK fail to fulfill its obligations or abide by the agreements. Further obligations include real-time data sharing on the movement of goods, the building of new border-control posts for the “red-lane” goods at NI ports, and perhaps most saliently, the UK’s agreement to withdraw the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill; legislation that would have granted the UK parliament power to unilaterally re-write the protocol.

Prime Minister Sunak has asserted apropos of the new framework that only the bare minimum of EU law will apply to NI as necessary to avoid a hard border with Ireland, and to allow NI businesses ongoing and fair access to the EU market. Despite the agreement’s assurances and those of its negotiators, The Windsor Framework has failed to assuage its harshest critics, who continue to aver that fundamental problems remain unaddressed; citing, for example, post-Brexit checks at ports of entry rather than along the Northern Ireland-Republic of Ireland border, arguing that ‘sea border’ restrictions will benefit all-Ireland trade, hence EU trade. Additionally, critics suggest that the framework has left NI vulnerable to regulatory incompatibility and disjunction with the rest of the UK market in order to accommodate EU trade rules, and that it obliges NI firms to observe EU laws on goods transported solely within the UK. Indeed, the UK’s growing regulatory divergence from EU practices and standards presents a future challenge for the durability of the framework’s arrangements, and could create new barriers for trade between NI and the rest of Great Britain, as well as the EU. Thus, the status and proper role of EU law functioning alongside NI’s political structures is an issue unlikely to abate under this framework alone. Although the framework creates greater transparency as to how EU law will be applied in the region, it cannot account for every future contingency that may arise, thus leaving open the possibility of reigniting hostility toward the EU if the current arrangements do not adequately benefit NI.

The Windsor Framework has also failed to improve the ongoing Stormont blockade situation, pushing Northern Ireland into its second year without a functioning government, and imperiling the future of the Belfast Agreement in its totality. Following promulgation through the House of Commons on March 22 – the framework now formally being adopted by both the UK and the EU – DUP leader Sir Jeffrey Donaldson confirmed that the party will not rejoin power-sharing at Stormont, and informed the House of Commons in March that The Windsor Framework did not fully restore Northern Ireland’s place within the UK. In contrast, DUP counterpart Sinn Fein’s ultimate political goal remains Irish reunification – such an eventuality likely involving NI fully re-joining the EU –, thus they have welcomed The Windsor Framework and are not ideologically opposed to being subject to EU laws.

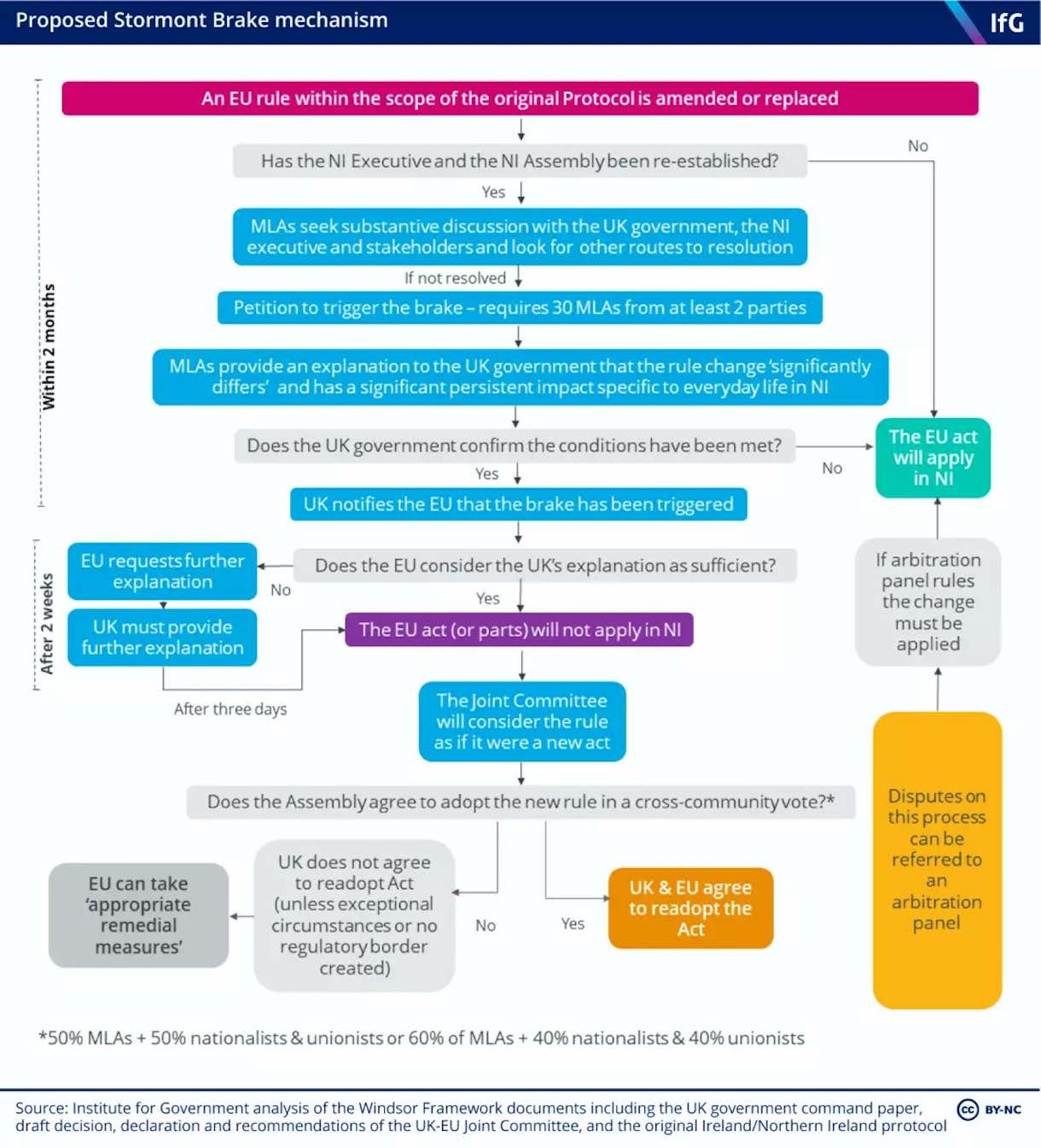

The ongoing disarray of Northern Ireland’s government notwithstanding, the framework provides little assurance that a future disagreement over EU laws will not cause a further breakdown in NI’s governance. Although the amended Stormont Brake rule aims to address such an eventuality, there is no guarantee that NI’s political parties will accept the outcome of its use, which could once again break the power-sharing agreement and halt government. Some have argued that the Stormont Brake contrivance is essentially useless as veto power ultimately resides with London, not Belfast. Thus, further recourse for NI’s political representatives in securing new concessions on the framework appears limited, as neither Brussels nor London have indicated any desire to reopen talks or renegotiate this agreement in perpetuity.

Wider political implications, contingent on the success of the new framework, exist for all parties involved, including future cooperation between the UK and EU on defence and foreign policy alignment, energy security, credibility with the US as future partners and in fulfilling the obligations of the Belfast Agreement, securing stability for investment into the region, etc. Any future success in addressing such issues may indeed rest on the efficacious cooperation in executing the new framework’s arrangements, as much has been agreed to under a good-faith understanding, however, with little practical experience in implementation. This raises the question of whether trust and co-operation between London and Brussels will be enough to sustain the agreement sans further fallout, in what has been an oft tense post-Brexit relationship between the two governments.