‘Incredibly resilient’ nylon device creates electricity under tonnes of pressure

RMIT University researchers have developed a flexible nylon-film device that generates electricity from compression and keeps working even after being run over by a car multiple times, opening the door to self-powered sensors on our roads and other electronic devices.

European research lays the groundwork for future stem cell clinical trials

RMIT has contributed to an international consortium exploring how human mesenchymal stem cells could help to repair brain injury in children born preterm.

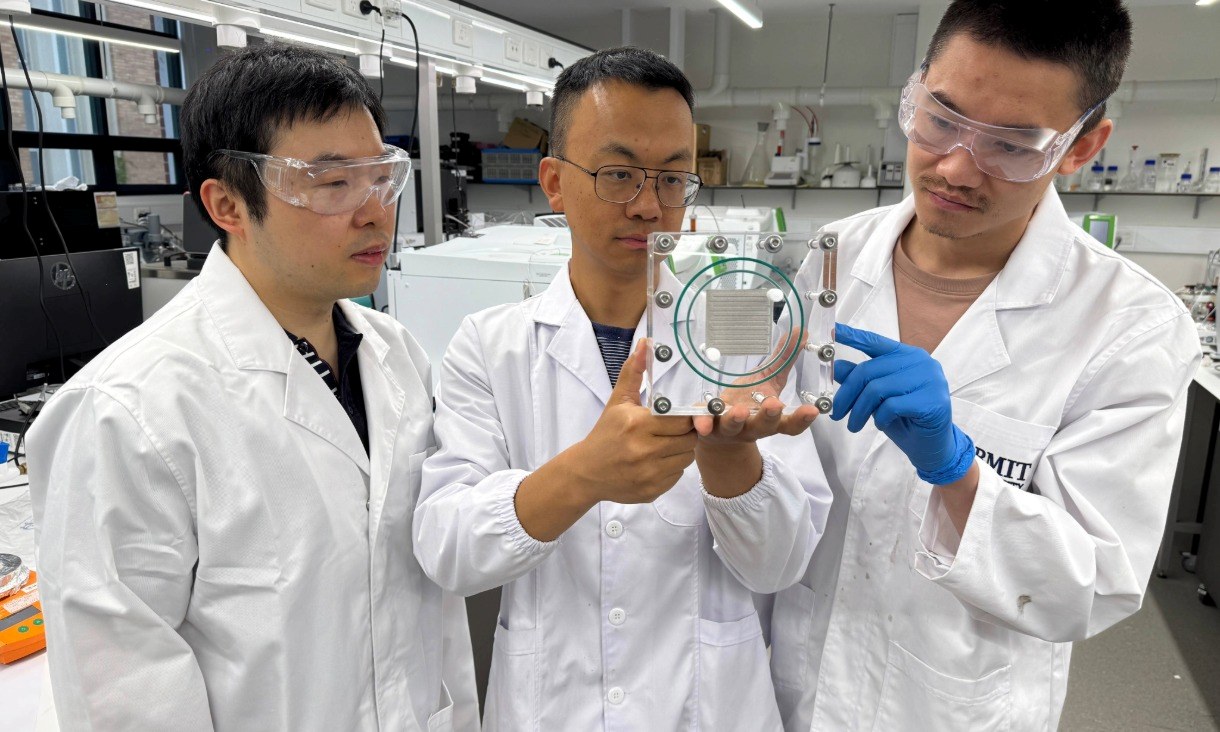

New carbon-conversion technology could turn emissions into jet fuel

RMIT researchers have developed a carbon conversion technology that may one day help turn industrial emissions into jet fuel, by simplifying how carbon dioxide is recycled.

Newly awarded Distinguished Professorships recognise excellence in research and leadership

Nine academics from across RMIT University have received the high honour, which is awarded to Level E academics who have achieved outstanding impact throughout their career.