‘Incredibly resilient’ nylon device creates electricity under tonnes of pressure

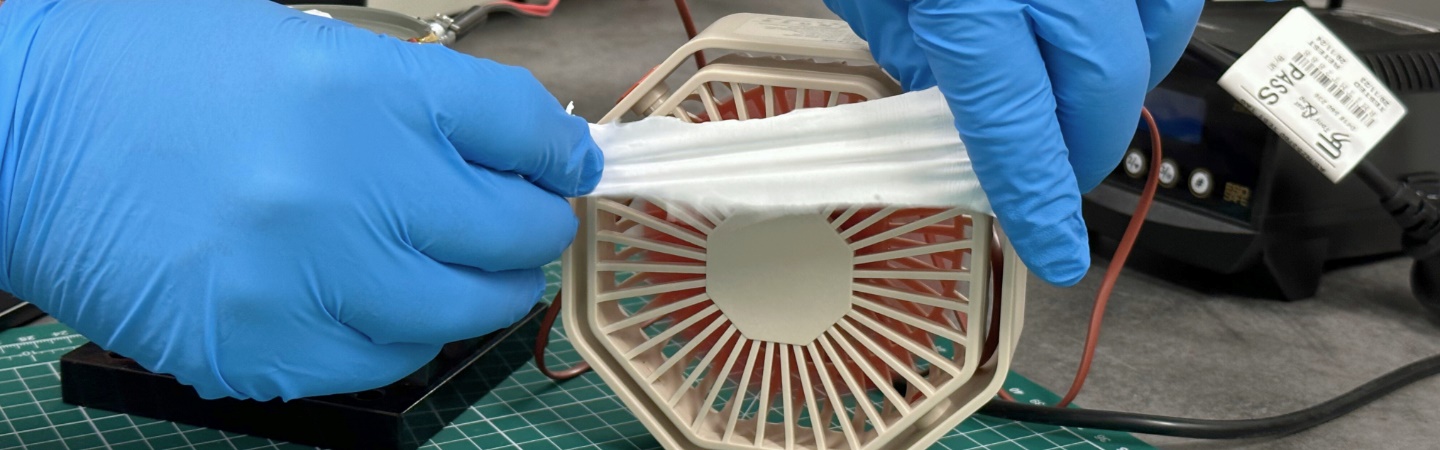

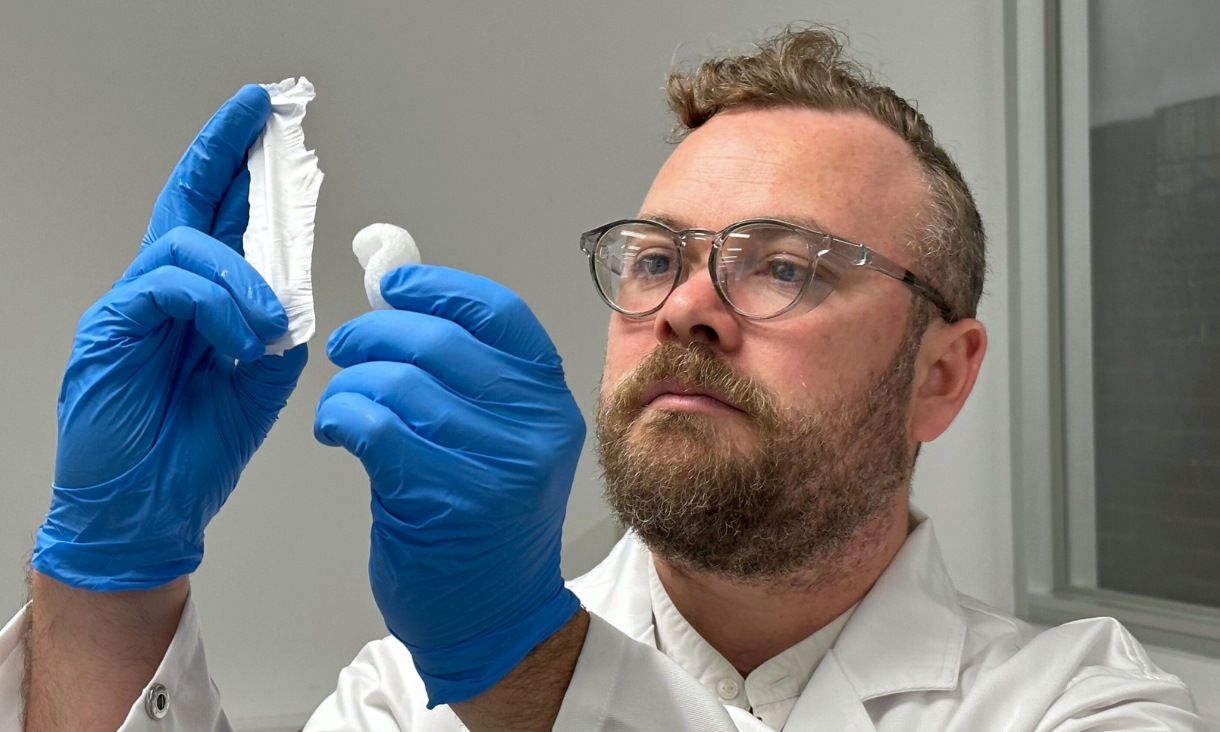

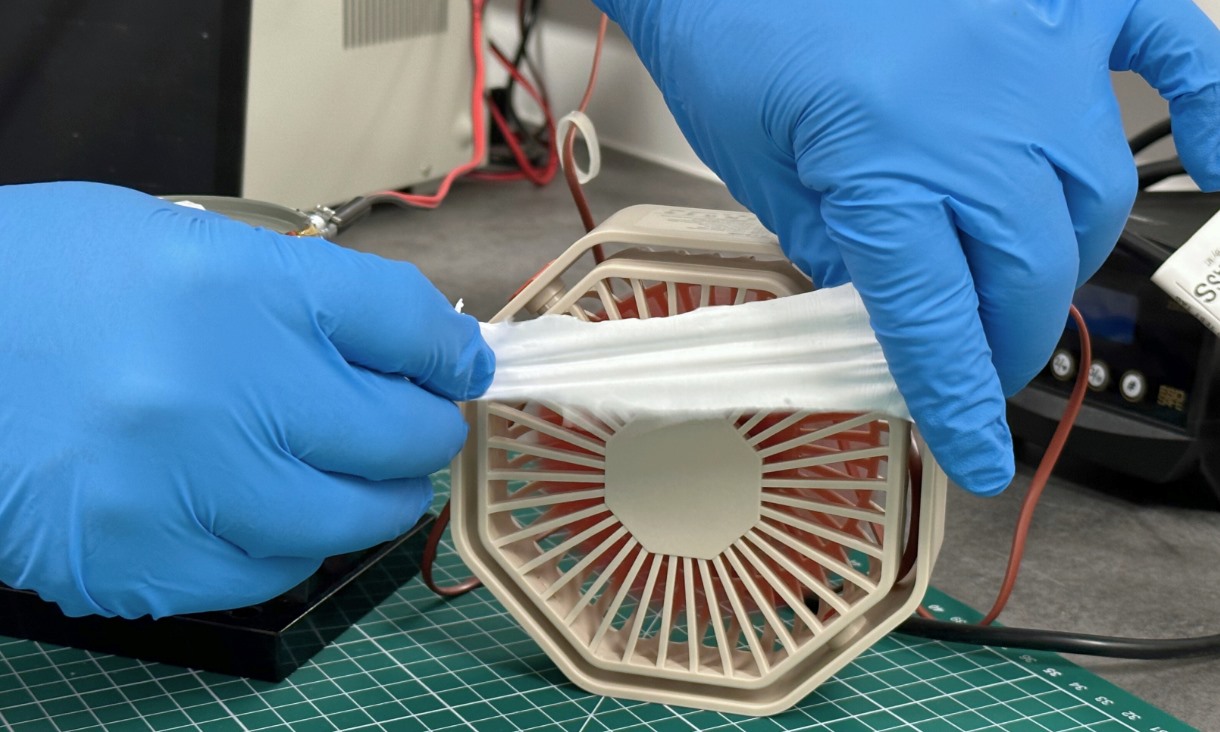

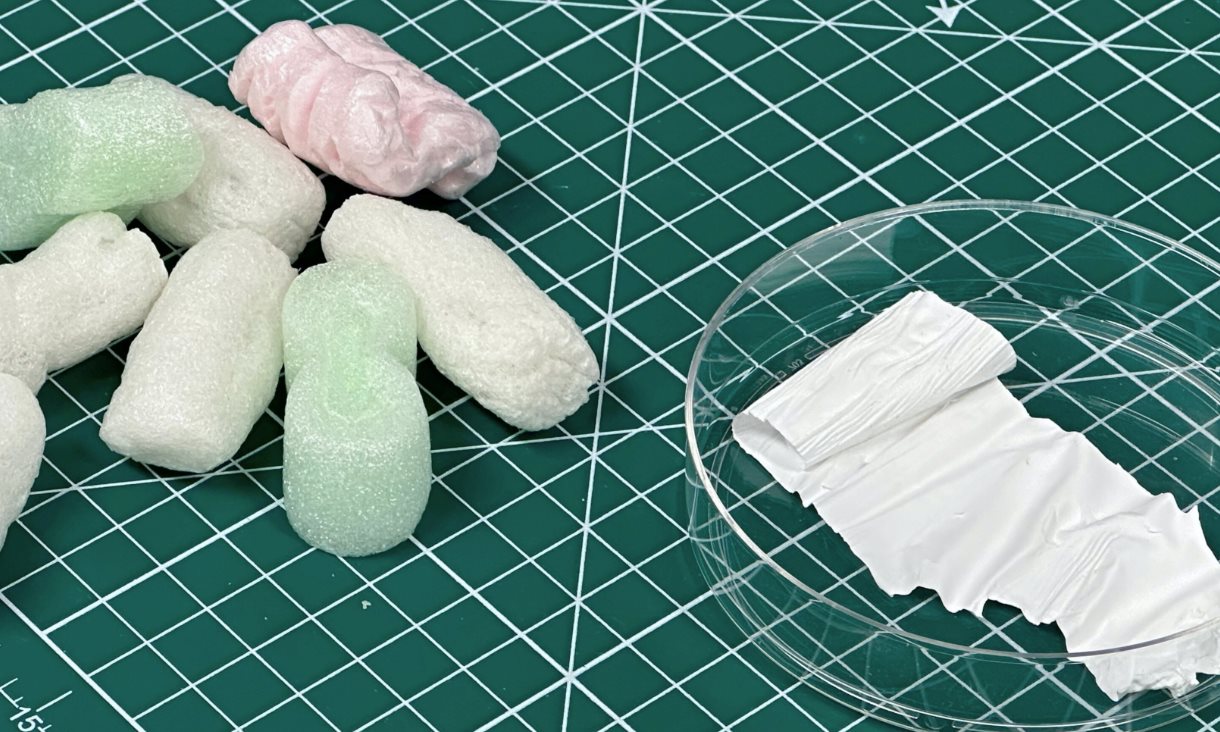

RMIT University researchers have developed a flexible nylon-film device that generates electricity from compression and keeps working even after being run over by a car multiple times, opening the door to self-powered sensors on our roads and other electronic devices.

European research lays the groundwork for future stem cell clinical trials

RMIT has contributed to an international consortium exploring how human mesenchymal stem cells could help to repair brain injury in children born preterm.

Aussie bushfire prevention tech goes global

A powerline fault detection system invented at RMIT is being rolled out globally thanks to AUD $50 million in new funding.

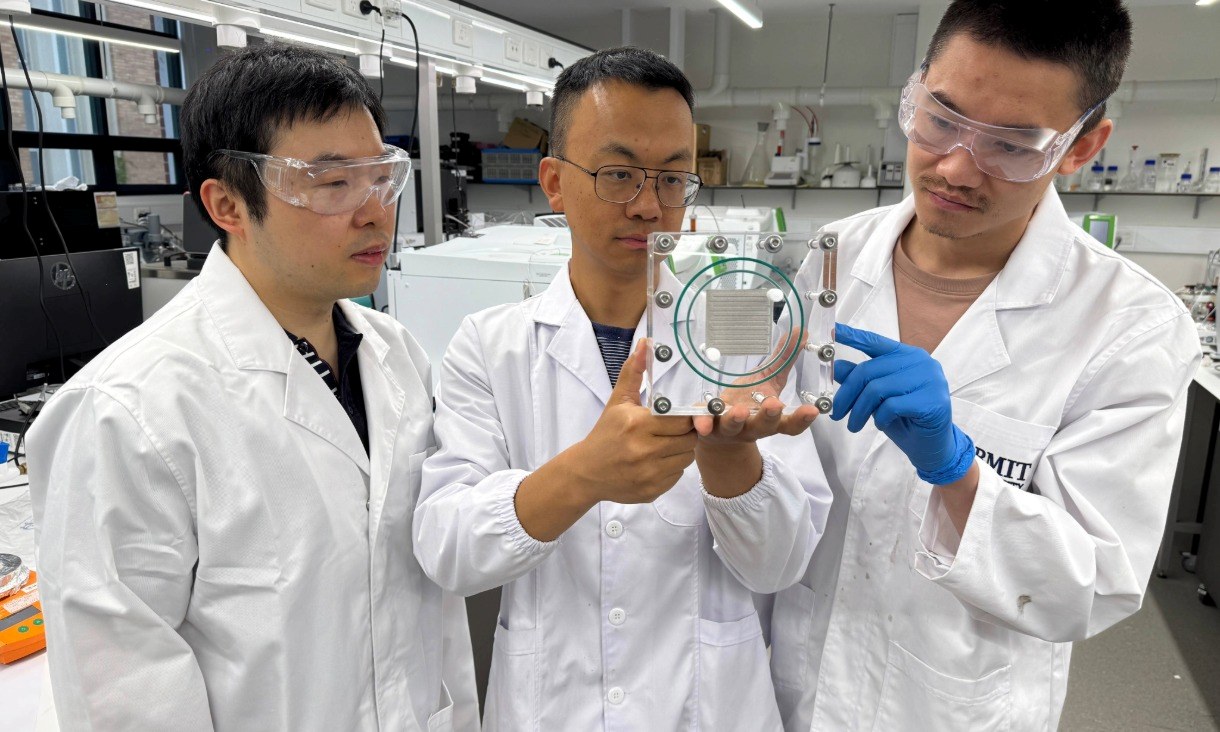

New carbon-conversion technology could turn emissions into jet fuel

RMIT researchers have developed a carbon conversion technology that may one day help turn industrial emissions into jet fuel, by simplifying how carbon dioxide is recycled.