Dr Lisa Cianci shares insights from two recent events, highlighting how artificial intelligence is now driving transformative change at the heart of higher education.

When the winds of change blow, some build walls… others build windmills.

- Chinese proverb

Story by: Dr Lisa Cianci | Manager, Library Digital Learning

This quote embedded in the THETA conference title stuck with me as I reflected on two recent events I attended: the THETA 2025 Winds of Change conference in Perth (May) and CAVAL’s AI-Driven Metadata Futures at RMIT (July), both of which placed AI firmly at the centre of higher education’s transformation agenda.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is no longer a peripheral innovation in academic libraries. Though many presentations weren’t exclusively about AI at THETA, at least half referenced it. AI wasn't just a popular topic at THETA, it was the undercurrent.

Whether framed through metadata workflows, copyright complexities, library chatbots, teaching and learning tools, or institutional governance, the message was clear: we’re no longer debating if AI matters, we’re now working out how to live with it, shape it and steer it.

Simulated intelligence, real responsibility

At the CAVAL event, academic librarians shared candid stories of trial, error and experimentation with AI LLMs (large language models).

Tools like ChatGPT and Transkribus are being used to assist in cataloguing, classification, transcription, language romanisation and schema mapping, while platforms such as Alma Specto have built-in AI which can assist with these functions.

Some are exploring AI tools to reclassify collections with problematic Dewey numbers. Others are using it to describe rare cultural artefacts. The potential is evident; however, so are the limitations.

Large language models don’t understand the structure or semantics of metadata in a meaningful way. They can summarise, mimic and predict but they cannot reason. They often hallucinate, guess or confidently deliver plausible nonsense. As many speakers noted, their use demands careful oversight. Human expertise is essential for accuracy, context and ethics.

At its best, AI gives library professionals a head start, especially on tedious or unfamiliar tasks. At its worst, it can mislead, misclassify or replicate bias. This tension defines our present moment: balancing productivity with integrity.

Photograph by Lisa Cianci at the UWA Reid Library

Photograph by Lisa Cianci at the UWA Reid Library

Copyright, containers, and the Library’s evolving role

Trish Hepworth’s ‘Copyright, Collections and AI’ session at THETA opened a broader conversation around how legal frameworks are being tested by emerging technologies.

Copyright has long shaped how university libraries collect, preserve and share knowledge – often invisibly. Now, with AI tools embedded in vendor platforms and contracts, the rules are changing again. As Hepworth framed it: “Control the container, control the knowledge.”

Libraries must now navigate multiple tensions: copyright versus open access, privacy versus innovation and data sovereignty versus automation. AI-generated outputs raise difficult questions about authorship, licensing and metadata transparency. Bots crawl repositories. Generative AI tools suggest citations that don't exist. Contracts sneak in terms we may not fully grasp.

The rise of generative AI challenges our assumptions about authorship, access and preservation. Who owns an AI-generated description? What responsibilities do we have if those outputs are incorrect or biased? What does metadata transparency look like in an AI-rich future?

These are pressing questions, especially as we continue to build discovery systems, open access platforms and digital learning repositories. The shift from descriptive labour to algorithmic authority means that libraries must urgently interrogate where data is coming from, who is training these tools, and how rights are being protected or violated. This is especially important for Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP), moral rights and privacy.

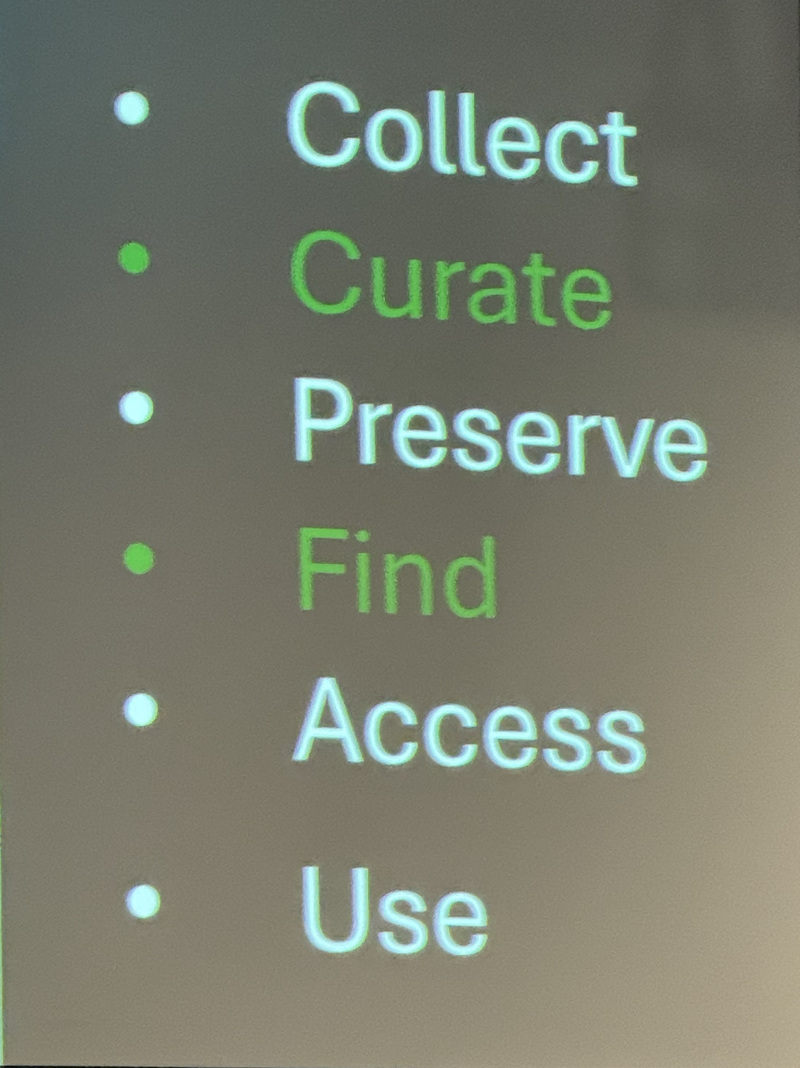

Image from THETA presentation: Trish Hepworth, Copyright, Collections and AI

Image from THETA presentation: Trish Hepworth, Copyright, Collections and AI

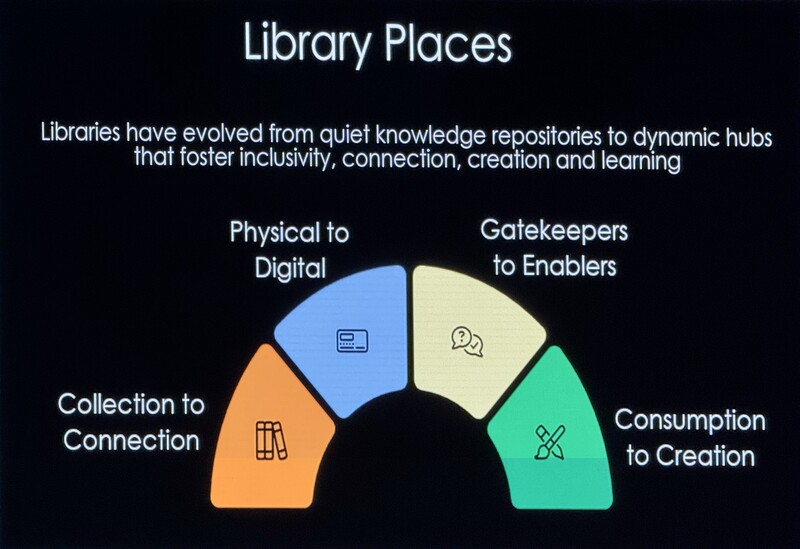

Libraries as hubs of digital transformation

Libraries were recognised at both events as essential transformation hubs. We’re uniquely positioned bridging academic, legal, technical and cultural knowledge. But with that comes increased pressure to lead responsibly.

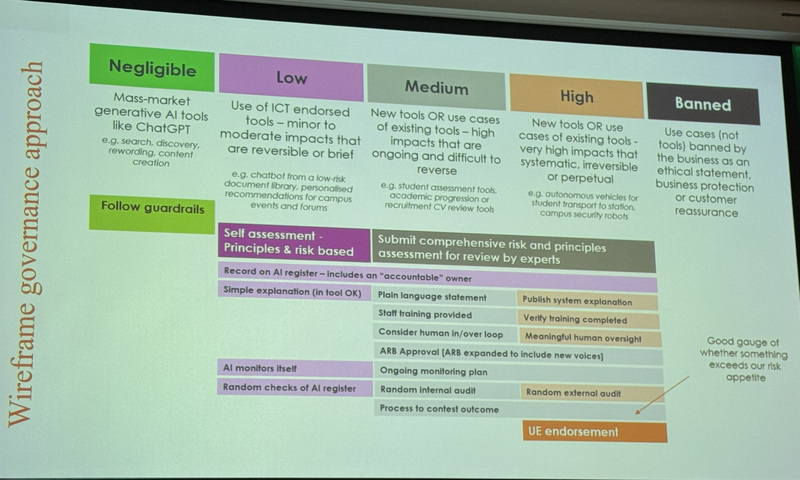

One highlight from THETA was the University of Sydney’s journey in building institutional AI capacity. What started as an innovation team pilot quickly grew into a university-wide effort involving many departments including Legal, Records, Ethics, Educational Innovation and Library Services.

Their story reminded us that you don’t need to start big to make an impact. However, you do need leadership, training and governance.

In Galen White’s presentation ‘Accelerating Digital and AI Transformation in Higher Education: Introducing the Higher Ed Service Portfolio Model’, the ‘crawl, walk, run’ digital ambition model is helpful here.

Image from THETA Presentation: Jill Benn, Transforming Together: People, Place and Change, UWA

Image from THETA Presentation: Jill Benn, Transforming Together: People, Place and Change, UWA

We all start somewhere. Digital literacy, information literacy and AI literacy are now foundational skills – not just for students, but for staff also. The University of Sydney focused not only on prompt engineering or tool usage, but also on data integrity, ethical reasoning and change resilience.

The concept of change literacy is essential here. This decade might be the most transformative we’ve ever experienced. The pace will not slow, so we need to prepare ourselves, and our students, to adapt with awareness, curiosity and care.

Student expectations, learning and equity

Another theme emerging at THETA was student digital literacy. More than half of students reportedly don’t know how to fact-check AI outputs. Many are using tools like ChatGPT, but without understanding the limitations. There’s also concern around fairness and academic integrity.

The broader takeaway? We need to embed AI literacy not just in isolated sessions, but across the full student journey from research to assignment preparation, to peer collaboration and citation. That includes understanding copyright, ethics, limitations and the social impact of these tools.

The Digital Literacy Framework outlined by Dr Nicole Johnston (Edith Cowan University) at THETA included five pillars:

- Digital proficiency

- Information, media, data & AI literacy

- Digital learning

- Digital communication & creation

- Digital citizenship, identity and wellbeing

If we want to prepare students (and staff) for the future, these areas must be scaffolded and sustained.

Chatbots, data, and learning analytics

AI isn't just entering metadata – it’s shaping our student services. Several sessions discussed the implementation of library chatbots.

The key takeaway? They’re not magic. They require significant staff time, testing, iteration and humility. They're useful, but not universally effective, and they still require human escalation for complex queries.

Meanwhile, data analytics from platforms like Canvas offer insight into student behaviour but not the whole picture. As one presenter asked, “Where is the learning?”

We need to find evidence of transformational learning experiences, but until we build systems of trust that let students share feedback meaningfully, our data will remain slanted and incomplete.

Image from THETA presentation: Jim Cook, University of Sydney, Navigating the Generative AI Journey: Collaborative Innovation and Leadership at Sydney

Image from THETA presentation: Jim Cook, University of Sydney, Navigating the Generative AI Journey: Collaborative Innovation and Leadership at Sydney

What's missing? Digital sustainability

One personal observation from THETA, there was little discussion around sustainable digital preservation – a surprising omission, given the explosion of digital content being created. As a professional information and knowledge worker who is leading the RMIT Library Learning Object Repository (LOR) project, I find it troubling that we aren’t yet addressing how all this material will be kept, re-used or made meaningful in the long term. It was surprising that the long-term stewardship of digital content barely registered.

There’s a disconnect here: we’re creating more digital content than ever – videos, simulations, AI-generated materials. However, we’re not yet investing in the infrastructure or policy frameworks to ensure that content remains usable, findable and contextually understood in the future. Without governance, curation and preservation strategies, we risk losing the very knowledge we’re trying to expand.

Perhaps at the next THETA in Melbourne (2027), digital preservation will move closer to the centre of the conversation. I hope so. In the meantime, the Library’s Digital Learning Team continue with our work in digital stewardship and sustainable knowledge containers for learning resources in the AI era.

Final thoughts: Windmills over walls

If there’s one thing these events made clear, it’s that AI is not a threat, oracle or saviour – it’s a toolset. And like all tools, it reflects the values of those who wield it.

There’s a growing understanding that AI won’t replace librarians and knowledge workers in general, but it will change the work, and it’s already happening. More importantly, it’s highlighting issues with the systems, assumptions and knowledge containers we’ve inherited.

We don’t get to opt out of AI, but we do get to shape how it’s used. That means investing in staff skills, sharing critical insights, asking uncomfortable questions and building ethical frameworks that protect both people and knowledge. Knowledge workers, educators, technologists and policymakers are all now part of this digital transformation. If we stay committed to ethics, equity and evidence, we can hope that transformation serves our communities.

It also means recognising where we still need to do more, particularly around long-term digital stewardship, Indigenous metadata sovereignty and open, collaborative development. As one CAVAL panellist reminded us: “Don’t forget the human and don’t humanise the AI.” The future of libraries is deeply human, complex and possibly uncertain. Our work now is to move forward with clarity, care and critical optimism.

Highlight sessions I attended

There were so many concurrent streams at THETA it was difficult to choose!

THETA Winds of Change:

- Can Higher Ed Tell a Better Story? Monday keynote, Sisonke Msimang

- Tour of UWA Reid Library

- Navigating the Generative AI Journey: Collaborative Innovation and Leadership at Sydney, Jim Cook, University of Sydney

- Copyright, Collections and AI, Trish Hepworth, ALIA 3

- Transforming Together: People, Place and Change, Jill Benn, UWA

- A Model Indigenous Engagement Program, Derek Knox, Dell Technologies (laptop lending with indigenous designs TAFE NSW)

AI-driven Metadata Futures:

- Preparing Ourselves for Ethical AI Futures: Strategies for Investigation, Experimentation, and Development, Professor Lisa M. Given, RMIT

- Using AI Tools in Collection Description

Gemma Steele, Metadata Coordinator, Monash University Library - Saving Time: the Cataloguer’s Guide to Getting Things Done

Giuliana Tarascio & Lorraine Heller-Nicholas, Senior Metadata Officers, The University of Melbourne Library