My name is Professor Milan Brandt.

I'm a professor of advanced manufacturing at RMIT University, and I'm also the technical director of our advanced manufacturing precinct.

My name is doctor Mark Coughlin. I'm a neurosurgeon with a particular interest in complex spinal surgery and field like 3D printing.

Before I met doctor Mark Coughlin, my quality of life was at a zero. The pain in my spine was an 11 out of 10 every day. It was chronic pain which impacted my entire life the way I thought, the way I felt, the way I moved.

Amanda was born with an unusual condition called a hemi vertebra, with one of her spinal vertebra on misshapen and partially formed.

And this leads to very severe imbalance in her spinal posture.

So I was a social person. I was working in rugby, working in corporate events. But as it got worse, I would go to work, get home from work, and I'd collapse. I would just take handfuls of anti-inflammatories.

We were quite frustrated using the traditional commercially available implants and that they weren't made to fit Abnormal Vertebra particularly well.

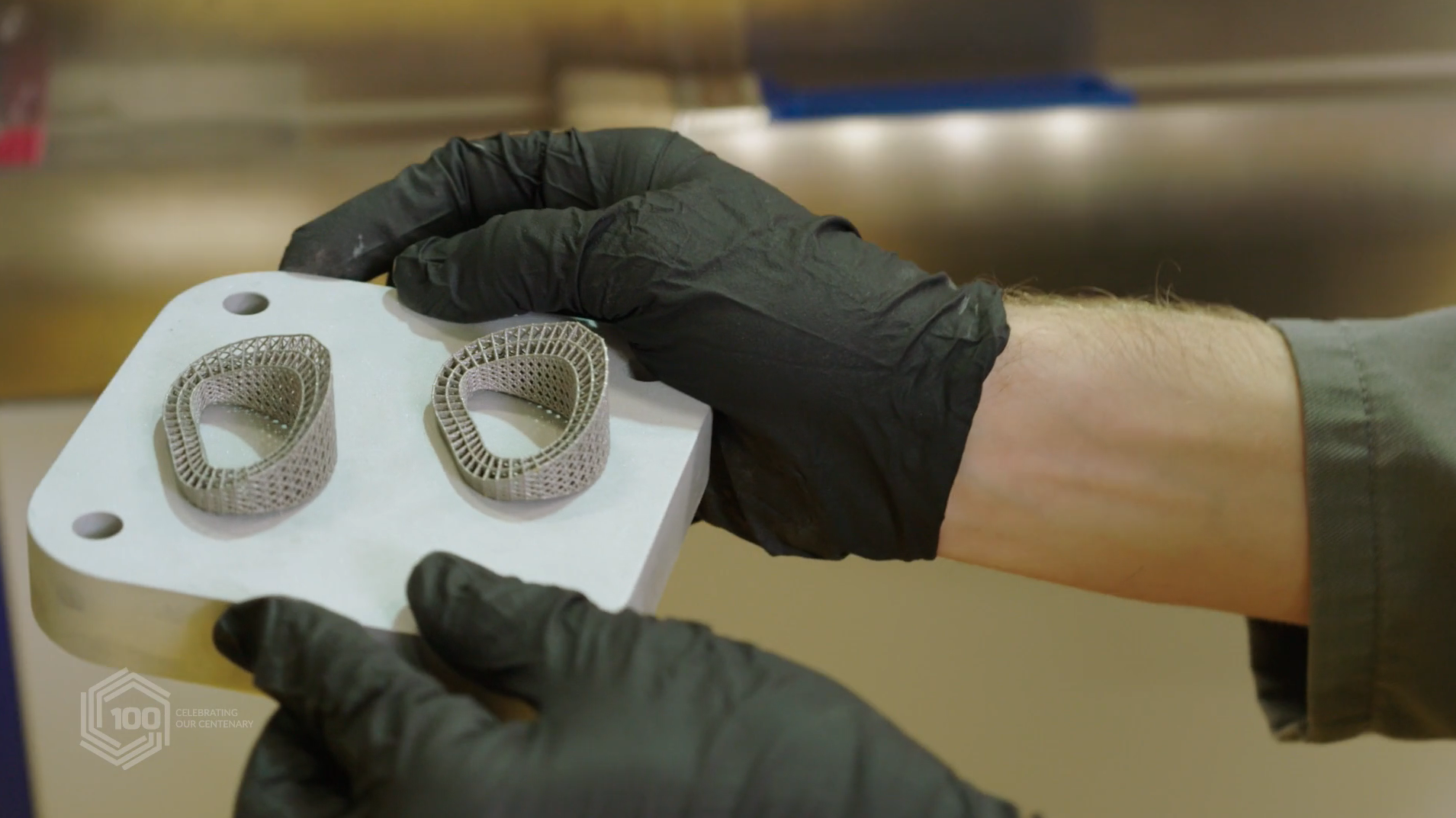

The complexity of the volume that it was trying to fill open an opportunity to use 3D printing with titanium to create an implant that would fit exactly into the space between her vertebrae.

Mark could see the state that I was in mentally and said, I'll fix you, and came back and proposed this solution of the 3D printing.

He said to me, you will be essentially a guinea pig. And I said, hit me with it. Some of the challenges in printing this implant involve designing structures that are non-uniform, that the lattice had to withstand something like six times the body weight.

RMIT were very proactive. We worked closely with them, trying to emulate a structure of the space that was very close to bone.

So they gave us a threaded titanium cage with this micro structure that Amanda's bone would grow and incorporate within that cage quite quickly.

The relationship with the surgeons and the engineers working together to develop my piece to the millimeter, perfect to go into my spine, was unbelievable.

The surgery went very smoothly. It was very exciting. When I put the implant into position, I felt it click into place like a key.

Apparently everyone in the operating theater breathed a sigh of relief because it was perfect.

Five days into rehab, I walked to the door for the first time. The first time I stood up, it felt like my spine was actually collapsing in on itself because it was straight for the first time in 40 years.

Then the next time I walked a little bit down the hallway. And Mark also gives you this feeling that, come on, you can do this.

We were absolutely thrilled that this was such a success, that this was really the first implant printed in Australia and implanted into a patient, and research we've worked on over many years in 3D printing was able to be used in a practical sense.

When I first saw Amanda a few weeks after the surgery at follow up, she looked a lot taller. Shoulders were back and I was just to be honest, I was completely blown away.

Amanda was almost completely pain free. I can tell you right now I wouldn't be here if they hadn't done what they did.

So thank you. I feel so blessed and I would do anything for RMIT and Mark.

I've just had a baby 13 weeks old, so I'm didn't actually think that I'd ever be able to do that because of the issue.

This small piece is giving me my whole world back. Since our work with Amanda. Our research is taking us in the direction of designing new generation of implants for bone cancer patients.

And this technology allows us to save as much of the limb as possible. And it's quite incredible to see two different types of fields working together to save people's lives.

Who knows what the possibilities are in surgeries, with children, with limbs if they can fix this kind of thing?

What? What does the future hold for us?

It's incredible.